The Indian scholar Maulana Wahiduddin Khan (1925–2021) was the founder of a global da’wah enterprise that focuses on the distribution of Qur’an translations. We discussed his English Qur’an translation (which was co-authored with, and probably mostly produced by, his daughter Farida Khanam on the basis of his Urdu translation) last week.

Khan was a madrasa-trained ʿālim. He first translated the Qur’an into Urdu and Hindi and added a commentary in the form of footnotes which he subsequently translated into Arabic, suggesting a target readership of Muslims in South Asia and the Arab world. But when the English translation by his daughter Farida Khanam was published in 2009, this signaled the beginning of an intense flurry of multilingual publishing activity on the part of Goodword Books, the publisher co-founded by Khan, which was clearly aimed at a much wider readership.

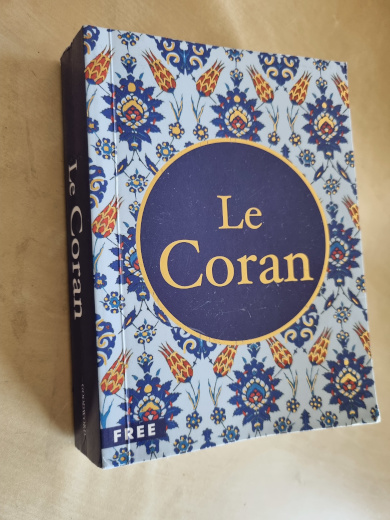

Goodword Books is based in India but prints its books in Turkey and distributes them from there. They offer Qur’an translations in a growing number of Indian and global languages, from Dutch to Korean, and from Ukrainian to Telugu, even including a Braille edition of its English translation. Some of these translations have been commissioned by Goodword, while others are licensed editions of pre-existing translations (such as the Ukrainian Qur’an translation by GloQur team member Mykhaylo Yakubovych). The books are available for download and the inexpensive, monolingual editions with their characteristic tile pattern are often given away for free, for example to tourists or at trade fairs. This reflects a general tendency towards a growing commitment on the part of private enterprises such as Goodword, the Saudi publisher Darussalam or the German Lies! foundation to da’wah through Qur’an translation, a field that had previously been dominated by state-funded institutions such as the Saudi King Fahd Qur’an Printing Complex in Medina or the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs.

The French translation we are focusing on in this post was published in 2017, apparently exclusively by Goodword, as a monolingual edition that contains a translation of Maulana Wahiduddin’s introduction and index but not the commentary and concordance that are available, for example, in the English and Urdu versions of his and his daughter’s translations.

The translator, Shahnaz Saïdi Benbetka, is one of only a few women to have translated the Qur’an. She was helped in the preparation of the translation by two family members; all three seem to be French Muslims with an Algerian background from the metropolitan region of Paris.

Saïdi clearly used Wahiduddin Khan’s and Farida Khanam’s English Qur’an translation as a template for her French one. This is visible, for example, in the way she renders the stories of Moses and Dhū l-Qarnayn in Sūrat al-Kahf (Q 18). She subtly inserts a minimal amount of additional information, such as the names of speakers on occasions where the Qur’an just says qāla (‘he said’), in exactly the same places as Khan and Khanam did, and she also follows their decision to use the Arabic term Dhu’l-Qarnayn (in this spelling), rather than translating it as ‘the Two-Horned one.’. She also often makes the same exegetical choices as Khan and Khanam, for example when translating the term awliyāʾ in Q 5:51 (‘O you who believe! Do not take the Jews and Christians as awliyāʾ) as ‘alliés’ where Khan and Khanam have ‘allies.’ Moreover, she follows Khan’s and Khanam’s choice against using the term ‘Allah’ for the Arabic allāh (instead: ‘God’/ ‘Dieu’).

However, there are also noticeable differences. Saïdi’s translation is more exegetical in style than that of Khan and Khanam. She seems to have taken cues from other French Qur’an translators that have led her to present a specific interpretation of Qur’anic expressions on a number of occasions where Khan and Khanam opted for a more literal rendition. For example, in Q 95:1, Khan and Khanam translate al-tīn wa l-zaytūn literally as ‘the fig and the olive,’ whereas Saïdi follows a widespread exegetical opinion that is reflected in many French Qur’an translations by rendering the terms as ‘the fig tree and the olive tree’ (‘le figuier et l’olivier’).

Or consider, for example, Q 2:2, where the Qur’an says about itself:

ذَٰلِكَ الْكِتَابُ لَا رَيْبَ فِيهِ هُدًى لِّلْمُتَّقِينَ

These are the English and French translations published by Goodword, respectively:

Khan/Khanam: ‘This is the Book; there is no doubt in it. It is a guide for those who are mindful of God.’

Saïdi: ‘Ce Livre au sujet duquel le doute n’est pas permis, est un guide pour ceux qui craignent Dieu.’ (‘This Book about which doubt is not permitted, is a guide for those who fear God.’)

In contrast to Khan and Khanam, Saïdi changes the syntax of the original and gives the ambiguous original a clear meaning. According to her, ‘no doubt in it’ (lā ghayba fīhi) means thatno doubt in the Qur’an is permitted, whereas Khan’s and Khanam’s rendition instead suggests that there is nothing in the Qur’an that gives rise to doubt, or simply that nobody would doubt the Qur’an. Moreover, Saïdi’s translation of the noun muttaqīn, which is derived from the root t–q–w and related to the central Qur’anic term taqwā, is distinctly different from Khan’s and Khanam’s: Saïdi opts for the commonplace translation ‘those who fear God’ (‘ceux qui craignent Dieu’) whereas Khan and Khanam, based on their spiritual approach, were clearly opposed to the idea that fear of God might be a virtue and therefore rendered the term as ‘being mindful of God.’

The most striking idiosyncrasy in Saïdi’s translation concerns the much-discussed ‘wife-beating verse’, Q 4:34, a verse that is traditionally understood to give husbands permission, or even instruct them, to hit their rebellious (?) wives (fa-ḍribūhunna). Khan and Khanam translate this imperative as ‘hit them [lightly].’ In his commentary, Khan includes a note on this verse that says: ‘The gender-based difference is meant only to ensure the effective management of worldly life and bears no relation to the requital and rewards of the Hereafter. […] However, under specific circumstances, if the man finds her guilty of immoral conduct, he should try to reform her. The process of this reform has to start with counselling, then if need be, he may cease to talk to and relate with her and lastly, he may reprove her with light punishment.’

By contrast, Saïdi translates fa-ḍribūhunna as ‘établissez une barrière entre vous et elles’ (‘erect a barrier between yourselves and them’), an interpretation that is in line with Muslim feminist discussions on Q 4:34.

Does this make Saïdi a feminist translator or is this an apologetic choice meant to prevent non-Muslims from gaining a negative impression of the Qur’an? At the very least, it is clear that Saïdi does not go out of her way to produce gender-neutral translations in other, less charged contexts. For example, like most French translators, she has a distinctly gendered translation of Q 4:1:

يَا أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ اتَّقُوا رَبَّكُمُ الَّذِي خَلَقَكُم مِّن نَّفْسٍ وَاحِدَةٍ وَخَلَقَ مِنْهَا زَوْجَهَا وَبَثَّ مِنْهُمَا رِجَالًا كَثِيرًا وَنِسَاءً

‘Ô vous les Hommes ! Craignez votre Seigneur qui vous a créés d’un seul être et qui, ayant créé de celui-ci sa compagne, fit naître de ce couple un grand nombre d’hommes et de femmes !’

(‘O you men! Fear your Lord who created you from a single being and who, having created from this [male] one his [female] companion, caused this couple to give birth to a great number of men and women.’)

The French language is more gendered than the English one, and finding a gender-neutral translation might have seemed like an unnecessary effort to a translator who, like most exegetes, obviously read this verse as a reference to the story of Adam and Eve. By contrast, many feminist exegetes have emphasized the gender-neutral language of the Qur’anic original, which does not imply at all that man was created first and woman was subsequently created from man. Feminists have also objected to the translation of Yā ayyuhā l-nās as ‘O men’ or ‘O mankind.’ Implementing their demands is possible even in French. For example, Maurice Gloton has proposed a gender-neutral rendering of the verse in his 2014 Qur’an translation:

‘Ô vous les humains ! Prenez garde à votre Enseigneur qui vous a créé d’une Âme unique. Il a créé d’elle son aspect conjoint.’

(‘O you humans! Beware of your Instructor who created you from a single Soul. He created from it its conjoined aspect.)

Saïdi, despite her take on Q 4:34, has thus not delivered an all-out feminist translation, and this might be one of the reasons why her work has not attracted much attention in France. Another reason might have to do with Goodword’s distribution network. While they hand out their Qur’an translations to tourists and at trade fairs for free and deposit them in hotel rooms, especially in Turkey, their books are barely, if at all, to be found in French mosques, Islamic bookstores or mainstream retail chains. Their Qur’an translations can indeed be downloaded for free but only in versions that do not contain the Arabic text, making them impractical for Muslims with a devotional interest in the Qur’an. Furthermore, while the printed versions are cheap, or even free, they do not come across as status objects either. And the lack of annotation means that their potential for furthering the reader’s understanding of the Qur’an is limited. Therefore, they probably rarely reach French Muslims, nor French non-Muslims with a serious interest in Islam. The impact of Saïdi’s translation is further limited by the fact that Goodword seems to have no distribution network in the French-speaking countries of West and North-West Africa. Ultimately, Goodword’s da’wah-oriented publishing and distribution style has the drawback that some of their products barely reach Muslim communities, especially in languages in which they produce no annotated bilingual editions. And yet, their translations get around and can be found all over the world – a Muslim equivalent of the Gideon’s Bible?

Johanna Pink