In 1935, the Orientalist publishing house Paul Geuthner in Paris published posthumously the last oeuvre of an exiled Turkish Muslim who had only just died of a heart attack en route from Alexandria to Europe. This work, a partial Qur’an translation titled La sagesse coranique (‘The Wisdom of the Qur’an’), was printed at the behest of the author’s widow, Princess Nimetullah (1875–1945), who was a daughter of the former Egyptian khedive Ismāʿīl. She also funded a translation into English, The Wisdom of the Qur’an, that was published in 1937 by Oxford University Press. The covers of both editions carried the Arabic quotation Li-kulli ajlin kitābun from Q 13:38, translated as ‘A chaque époque son livre,’ or ‘To every age its book.’

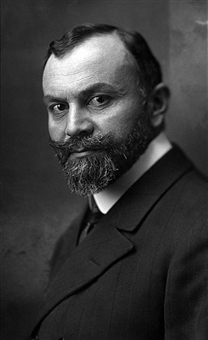

It is obvious from these initial remarks that the author, Mahmoud Mohtar Katirjoglou (in modern Turkish spelling: Mahmut Muhtar Katırcıoğlu), born in 1867, had led an illustrious life. He was a member of the Ottoman elite and was a cosmopolitan polyglot Mediterranean bourgeois. He was also a deeply religious man who considered it his mission to familiarize Europeans with what he considered to be the essence of Islam and its true teachings. Already in 1915, as Ottoman ambassador to Berlin, he had published a book that contained translations of selected Qur’anic verses and ḥadīths, arranged in thematic chapters. The work was framed by the publishers as a contribution to the Ottoman-German alliance in World War One, but to Mahmut Muhtar it was clearly predominantly a work of faith, meant to correct European prejudices about Islam and possibly even to proselytize. We have discussed this work, as well as Mahmut Muhtar’s career, in a previous instalment (https://gloqur.de/quran-translation-of-the-week-93-the-quran-as-a-weapon-in-the-great-war-mahmud-mukhtar-pasha-and-the-german-ottoman-alliance/).

(Mahmoud Mohtar Katirjoglou)

Between then and 1935, Mahmut Muhtar’s world had changed drastically. The Ottoman Empire had ceased to exist, and to the new Turkish Republic he owed little but the surname Katırcıoğlu, which he had had to adopt in 1934, when all Turkish citizens were required to adopt a surname. He had already quit the service of the Empire in 1917, a few years before it met its end, because he had fallen out with the government that was run by the Committee for Union and Progress, better known as the Young Turks. Disenchanted with the increasing turn towards Turkish nationalism, he left Istanbul, never to return, a decision that he had no reason to revoke after the establishment of the Turkish Republic which put him, along with other former members of Ottoman governments, on trial. He was convicted of the misappropriation of state funds because, during a short stint as Minister of the Navy, he had entrusted a large sum to a British company in exchange for works on the Anatolian railway. He spent the last eighteen years of his life in exile between Egypt and Europe. Cairo was, at the time, host to a considerable number of former members of the Ottoman elite, including religious scholars such as the second last şeyhülislam Muṣṭafā Ṣabrī, who was deeply hostile to the very notion of translating the Qur’an. This was not so with Mahmut Muhtar, as his final work shows.

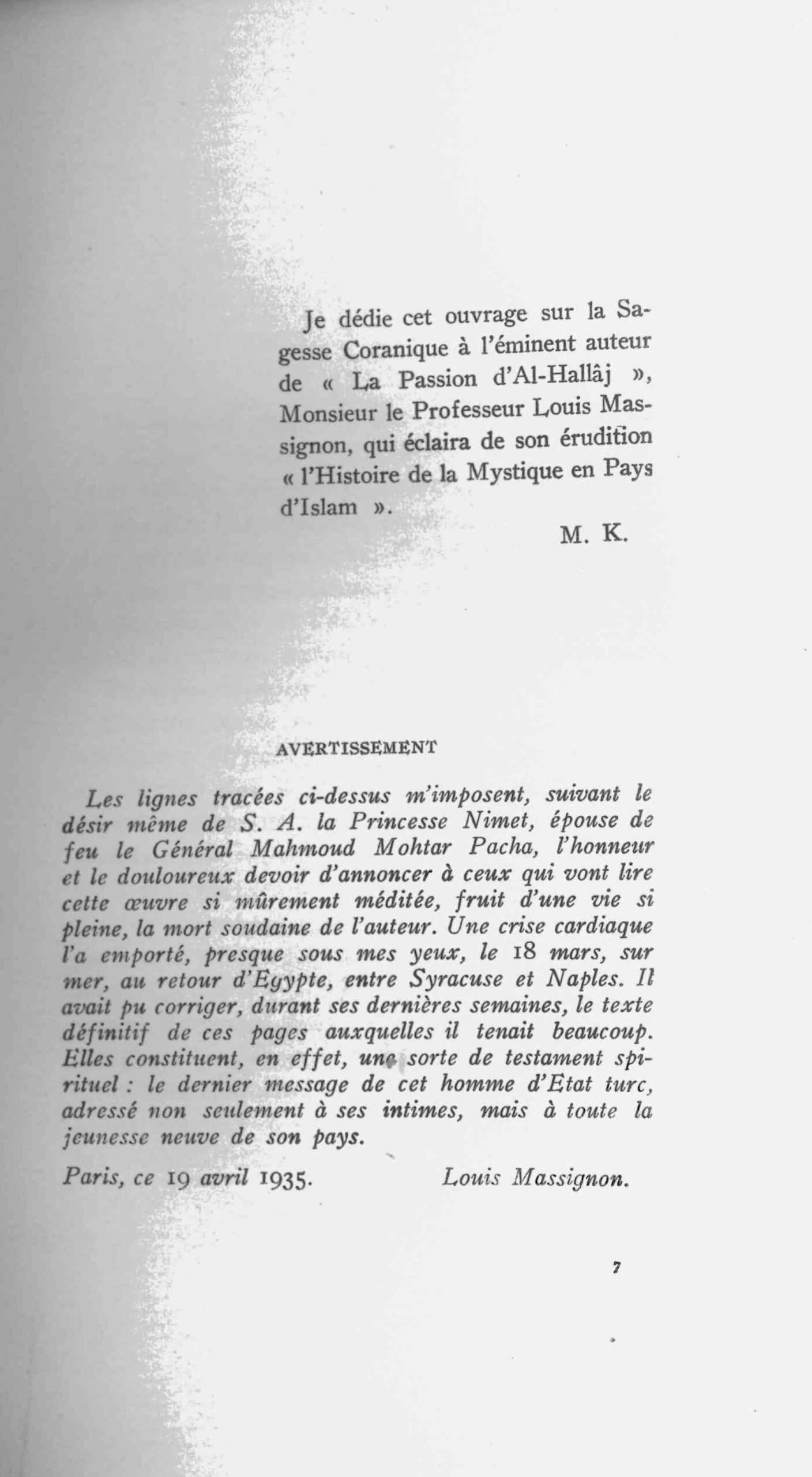

Fully titled La Sagesse Coranique: éclairée par des versets choisis reflétant la philosophie morale, religieuse et sociale de l’Islam (‘The Wisdom of the Qur’an: Elucidated by selected verses that reflect the moral, religious and social philosophy of Islam’), the book is dedicated to the French Orientalist Louis Massignon (1883–1962), a Catholic who, like Mahmut Muhtar, was engaged in promoting Christian-Muslim understanding. Massignon, in turn, wrote a brief foreword that indicates he was travelling with Mahmut Muhtar when the latter passed away on a ship between Syracuse and Naples. According to Massignon, the book was addressed ‘not only to his close friends, but to the entire new young generation of his country,’ which seems a bit strange, given that the book was written in French, not Turkish, and then translated into English, not Turkish, and both editions were published in Western Europe. Clearly, Mahmut Muhtar had more of an interest in proselytizing among European Christians than Massignon was ready to admit.

The book contains around 200 pages of translated verses from the Qur’an, arranged sura for sura in their canonical arrangement, and a lengthy ‘synoptic exposition of the teachings of the Qur’an’ of 45 pages. The exposition opens with the same quotation from Q 13:38 that is on the cover, allowing Mahmut Muhtar to present Islam as the continuation and completion of previous revelations. In the following pages he also introduces some basic doctrines of Islam, the biography of the prophet Muhammad, and his own view of Islamic history, which is based on the same narrative of decline and ossification that was common among European Orientalists at the time. According to Mahmut Muhtar, the decline ended only in the nineteenth century, under the influence of Western expansion, when the power of the ulama was challenged and Islam was reformed. In this context, he depicts the secular reforms of Republican Turkey, including the abolition of the caliphate, madrasas and Sufi orders, in an extremely positive light, despite the fact that he does not generally seem to have any problems with Sufism. It is clear that this favourable portrayal of the Turkish Republic served to underline the potential of Islam for European-style modernisation, regardless of the fact that Mahmut Muhtar had actually chosen not to live in that country.

The translation itself, according to Mahmut Muhtar, contains the ‘essential parts’ of the Qur’an, namely those of lasting religious, moral, philosophical and social value – approximately one fifth of the scripture. The remainder, in his opinion, mainly reflects and reacts to the changing and difficult circumstances in which Islam emerged, and is therefore of a conditional and temporally limited nature. He justifies the endeavour of retranslating a text that had already been translated so many times before by saying that it is precisely this multitude of translations that points to a need for improvement, especially since the translation of a sacred scripture requires more than purely linguistic skill. A philologically exact, literal translation, he feels, does not represent the source text’s rhythm and style nor the underlying values that it is based on. The extreme beauty of the Qur’an further contributes to the difficulty of doing it justice in translation.

What, then, does he consider to constitute the essential parts of the Qur’an, and which parts are inessential? First of all, no sura is entirely missing from his translation, with the exception of the last two, the muʿawwidhatān, which he may have considered mere prayers or may have disliked due to their allusions to superstition and magic. With regard to the remaining 112 suras, the number of verses he selected from each is entirely disproportionate to their actual length. His selection criteria are clearly related to their content.

It is obvious that he does not count verses related to warfare or those providing legal details among those that are eternally relevant. For example, while his selections from Sūrat al-Zumar (Q 39) take up more than five pages, both Sūrat al-Anfāl and Sūrat al-Tawba (Q 8 and 9), which allude to a number of battles and campaigns, amount to only one page each, even though they are significantly longer. Sūrat al-Baqara (Q 2) receives a fair amount of coverage (fifteen pages) whereas the suras al-Nisāʾ and al-Māʾida (Q 4 and 5), which contain a higher proportion of legal content, are not represented anywhere near as comprehensively.

Another category of Qur’anic material that Mahmut Muhtar is not interested in covering is narrative. For example, from the 129 verses of Sūrat Yūsuf (Q 12), which contains the longest uninterrupted story in the Qur’an, that of Joseph and his exile in Egypt, he selected no more than three verses; and from Sūrat Maryam (Q 19) which, among other stories, contains a version of the birth of Jesus, just four. From his selection, the reader would not even begin to guess that the suras (whose titles he generally omits) speak about biblical figures. Maybe he considered these stories to be merely repetition of biblical content for Arabs who were not familiar with it, or maybe he did not want to risk readers wondering about the obvious differences between biblical and Qur’anic material. If biblical prophets are mentioned at all in his selection, then it is as recipients of previous scriptures with content identical to the Qur’an, in order to underline the unity of all monotheistic religions.

Generally, Mahmut Muhtar’s focus is on God, faith, prophethood, revelation and the Hereafter, as well as some ritual and ethical prescriptions such as fasting, undertaking the pilgrimage, or caring for orphans. With the exception of matters of ritual, the only legal issue that comes up occasionally is marriage. He translated a few verses with specific rules about marriage and repudiation (Q 2:221, 4:3, 5:5 and 65:7), without any attempt to gloss over expressions that might be cause for polemics, such as the mention of slaves in Q 2:221. Q 4:3, which gives men permission to marry up to four wives, is one of the few verses that is appended with an endnote. Here, Mahmut Muhtar argues that the verse restricted the previously unlimited practice of polygamy and opened the way towards its complete prohibition, as was recently brought in in Turkey.

Regarding Q 2:223, a verse on marital relations, he openly acknowledges the existence of polemics. He translates it as follows: ‘Vos femmes sont pour vous un champ de culture. Approchez-vous-en pour ensemencer ainsi le vous désirez …’ (‘Your women/wives are for you a cultivated field. Approach it for sowing when you wish …’), and adds an endnote in which he comments that this verse was sometimes translated in an ignominious fashion that is in contrast with the Qur’an’s spirit. It is not quite clear what translation he is referring to here, because his own translation does not gloss over the potentially problematic implications of the verse either. This is evident when his original French translation is compared with the – generally fairly literal – English translation of this work by John Naish, who rendered Q 2:223 thus: ‘Let your wives be to you for a fruitful field. Be ye joined to them in marriage with a view of offspring …’ Apparently, Naish, or possibly Mahmut Muhtar’s wife, who had commissioned him, wanted to rule out the possibility of reading the verse as giving permission to non-consensual marital intercourse, something that Mahmut Muhtar clearly was equally uncomfortable with but unwilling to resolve by way of an overly interpretive translation.

In a few cases, Mahmut Muhtar makes exegetical interventions that are quite revealing. For example, he translates Q 2:184, a verse containing rules about fasting in Ramadan, in a way that suggests that it is possible to break the fast without a legally prescribed reason and that whoever does so can expiate by feeding the poor, even though fasting is better. With this translation, he positions himself with respect to a debate on this subject that raged in Turkey in the 1920s with an interpretation that was philologically justifiable, namely, that Muslims basically had a choice between fasting and almsgiving. This opinion was ultimately not very successful because it clashed with the consensus of legal scholars.

In another case, that of the ‘Throne verse’ (āyat al-kursī, Q 2:255), it is the opposite: Mahmut Muhtar opts for a metaphorical translation that is entirely in line with the predominant interpretation of Ottoman religious scholars who, as a rule, rejected any anthropomorphic description of God. Thus, when the Qur’an says that God’s kursī (‘seat,’ ‘stool’ or ‘footstool’) extends over the heavens and the earth, these theologians understood this to be a metaphorical expression denoting God’s knowledge or power. Accordingly, Mahmut Muhtar translates the relevant phrase as ‘Sa Domination embrasse les cieux et la terre’ (‘His Dominion embraces the heavens and the earth’).

Mahmut Muhtar might have made this choice not so much out of respect for the authority of religious scholars but rather due to a distaste for statements that might make Islam appear to be a superstitious belief system, based on the doctrine of a corporeal God who sits on a Throne that is located above earth.

A similar desire to frame Islam as a rational religion clearly informed his translation of Sūrat al-Fīl (Q 105), a very short sura which is commonly understood to refer to the story of an army from Yemen that attacked Mecca in the year of Muḥammad’s birth. Abdel Haleem translates the sura as follows:

‘Do you not see how your Lord dealt with the army of the elephant? Did he not utterly confound their plans? He sent ranks of birds against them, pelting them with pellets of hard-baked clay: He made them [like] cropped stubble.’

The mythological quality of this story disappears completely from Mahmut Muhtar’s unusual rendition:

‘Do you not know what your Lord did to the aggressors who were carried by elephants? Did he not turn their audacity into disaster, by rousing against them a succession of beings flying around in space? They attacked them with their poisoned stings, and rendered them to resemble leaves that are dried out leaves and eaten by worms.’

(‘Ignores-tu ce que ton Seigneur fit jadis des agresseurs portés par des éléphants? Ne tourna-t-Il pas leur audace en désastre, En suscitant contre eux une succession d’êtres voltigeant dans l’espace? Ils les assaillierent de leurs dards venimeux, Et les rendirent semblables à des feuilles desséchées et rongées par les vers.’)

In an endnote, he explains that the Abyssinian attackers were killed by a smallpox epidemic. Mahmut Muhtar thus transformed the birds (ṭayr) mentioned in the sura into air-borne viruses. This is a type of ‘scientific exegesis’ that was extremely common in South Asia and, to a slightly lesser extent, in the Ottoman realm. This specific interpretation of Sūrat al-Fīl was proposed by Muḥammad ʿAbduh in his Tafsīr juzʾ ʿammā, published in 1904, and it is quite likely that this was Mahmut Muhtar’s source. However, it is rare that interpretations of this kind are so directly expressed in Qur’an translations. Even Muhammad Ali, the head of the Lahore Ahmadiyya, who made a point of interpretating and translating Qur’anic miracle stories in a rationalistic manner, shied away from translating al-ṭayr as anything but ‘birds.’ Mahmut Muhtar, in contrast, had no such reservations. This was in line with the zeitgeist of the 1930s, and it was also an expression of his general view of Islam as compatible with modernity and progress.

It is on this note that he concluded his translation, commenting:

‘“Lis, car ton sublime Seigneur instruit par la Plume et enseigne à l’homme ce qu’il ne connaît pas” XCVI 3-5, dit le Coran. Les plumes furent toujours différentes et celles de demain semblent ne pas vouloir être pareilles à celles d’antan. Un verset, LV 22, dit en effet que la volition divine s’exerce constamment. Il proclame ainsi comme loi l’incessante évolution. L’horizon a beau être le même, chaque aurore y dépeint ses propres couleurs.’

‘“Read, for your sublime Lord instructs by the pen and teaches man what he does not know” 95:3–5, says the Qur’an. The pens have always been different and those of tomorrow would not want to be like those of the past. One verse, 55:22, in fact says that the divine will is constantly at work. It thus proclaims the law of incessant evolution. The horizon might always be the same, but each dawn paints it in its own colours.’

Johanna Pink