Although Lithuania, which has around three million native speakers of Lithuanian, has an indigenous Muslim population (known as ‘Lithuanian Tatars’) with a well-developed textual tradition of Islamic learning, this group mostly uses Polish instead of Lithuanian. Because of this, the first translation of the Qur’an into Lithuanian has only been published recently, in 2008: 1,000 copies were printed in total, and these sold very fast. The translation is from the hand of Sigitas Geda (1943–2008), a Lithuanian poet and translator, and also a well-known politician, both in Soviet times and after Lithuanian independence. A graduate in Lithuanian Language Studies from Vilnius University, Sigitas Geda is one of the best-known Lithuanian writers of the Soviet and post-Soviet generations of authors and poets. In his later years, according to a number of interviews, he became interested in the literature of the East, and this finally led him to translate the Qur’an into Lithuanian, as an attempt to enhance the cultural understanding of this text among the local populace. Never formally trained in Arabic, it is said that Sigitas Geda consulted a number of scholars during the translation process. However, this does not change the fact that his translation is primarily based on Russian interpretations rather than the original Arabic: according to some reviews, he relied mainly on the Russian Qur’an translations by Gordii Sablukov (1878) and Ignatii Krachkovskii (1963). This was not a rare occurrence in the post-Communist space: even after the collapse of the USSR and the Eastern bloc in general, Krachkovskii’s translation, a work of Soviet oriental studies, was a major source used for ‘re-translation’ of the Qur’an into many languages, from Bulgarian to Uzbek.

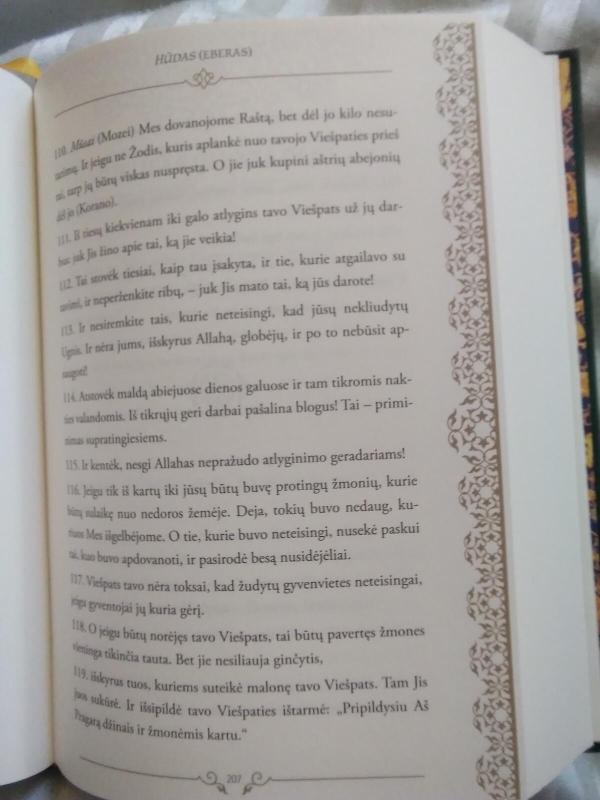

In the last month of his life, prior to his death on 12 December 2008, Geda faced an unexpected barrage of criticism when his translation first appeared in print. First of all, a few Muslim activists, most of whom were members of the Arabic diaspora in Lithuania, published negative reviews on local websites, claiming that the translation misrepresented the vocabulary of the Qur’an. They pointed out that some words had been completely transformed, such as ‘al-jinn,’ which became ‘the geniuses’ (‘genijai’), while others were translated in a improbable fashion: thus ‘dābbat al-arḍ’ from Q 34:14 was rendered as ‘mole’ (‘kurmiu’) rather than ‘worm’, ‘earthly animal’ or something similar. Likewise ‘al-ḥūt’ (Q 37:142) was interpreted as ‘the shark’ (‘rykliu’) rather than ‘the whale’ or ‘fish’ as it usually is. The treatment of some other elements, according to the Lithuanian Islamic studies scholar Egdūnas Račius, is also problematic: for example, the female pagan deities mentioned in Q 53:19–20 are described in Geda’s translation as male, while the Holy Mosque of Mecca (al-masjid al-ḥarām, Q 2:144) is described as ‘Uždrausta’ (‘the Forbidden One’). Although one of the meanings of the word ḥarām is ‘forbidden’ (and Geda probably simply followed the Russian translation of Ignatii Krachkovskii here), for the Lithuanian reader unfamiliar with Arabic and Islam, this description of the mosque would seem very bizarre.

Such misunderstandings and shifts in meanings are almost certainly related to the fact Geda based his translation on other translations rather than the original Arabic; as a poet himself, Geda was more interested in producing a highly eloquent target text than engaging with any exegetical discourses or historical debates. Some of the reviews produced by those in academic circles were also critical of his translation, and probably the only person who saved this work from being completely dismissed was the mufti of Lithuania, Romas Jakubauskas. He expressed a constructive desire to revise the translation, and due to his involvement, after just two years a new, revised edition with many changes was published in 2010. A few reprints of the same revised edition appeared later,. These included the addition of Jakubauskas’ name as a second translator, and, moreover, formal ‘approval’ of the translation by the Muftiate, the highest religious authority in Lithuania. The problematic translations have been largely corrected in the revised version, and the newest edition of Koranas also contains a few footnotes and insertions to the core text (indicated by brackets). The first complete translation of the Qur’an into Lithuanian (a partial one was previously produced by the Ahmadi community in 1989, from Mawlawi Sher Ali’s English translation), Geda’s translation is still quite a limited source for those seeking enlightenment about the meaning of the Qur’an in their own language. The second edition, though introduced and edited by local Muslims, remains a problematic text which was initially based on a language other than Arabic. However, with no other alternative currently available, it continues to be cited, even in academic works. Koranas is an interesting case, because it shows how religious ‘approval’ from an Islamic community can change the fate of a text, especially in areas where literature on the Qur’an available in domestic languages is scarce.

Mykhaylo Yakubovych