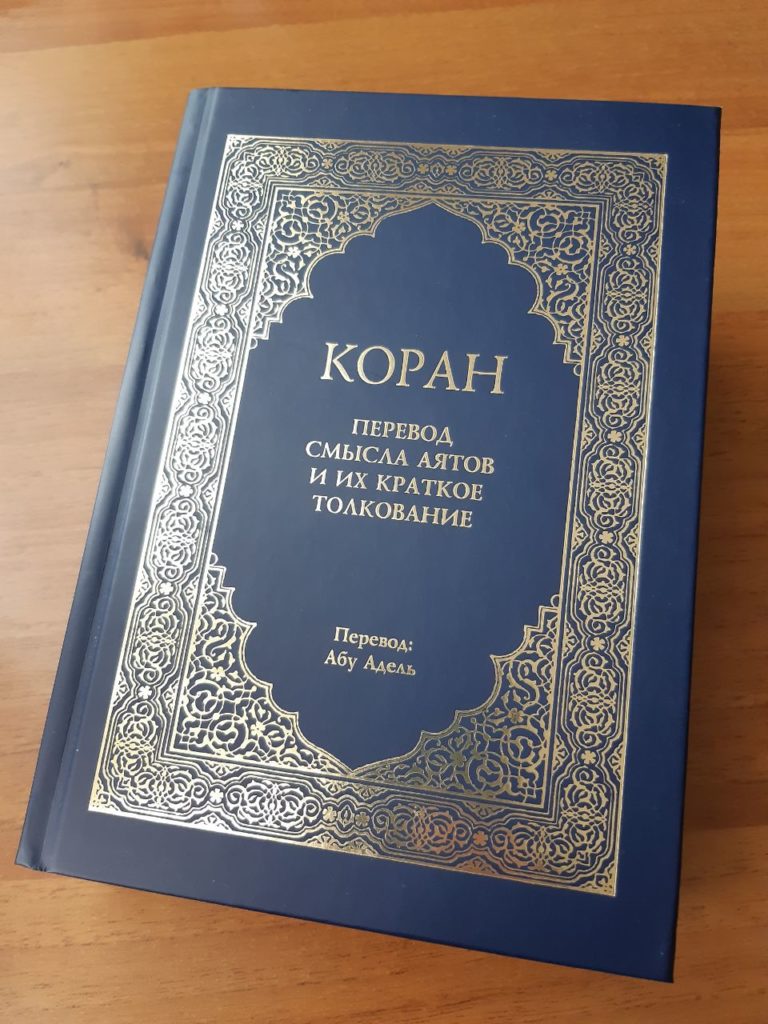

This week we turn our attention to Koran: Perevod Smysla Ayatov i ih Kratkoe Tolkovanie (‘The Qur’an: A Translation of the Meaning of its Verses, Accompanied by Concise Interpretation’), a Russian Qur’an translation by a Tatar translator known by the teknonymic name Abu Adel. First published in 2008, it is already on its fourth edition. Its main feature is the inclusion within its text of short interpretations based on the Saudi-produced al-Tafsir al-Muyassar (‘Simplified tafsīr’), which is the work of a group of scholars affiliated with the King Fahd Qur’an Printing Complex (KFCPQ). While the author, Abu Adel, has travelled to the Middle East subsequently, he originally taught himself Arabic while living in Russia and, moreover, has not studied Islam in an academic setting in either Russia or the Middle East. Instead, he studied privately with Idris Galavetdin (b. 1963), one of the most influential spokesmen of the Salafi community in Tatarstan (Bustanov, 2017). Galavetdin spent time studying Islam in Riyadh in the early 1990s, and is a prolific author of writings about Islam in the Tatar language (although his works have also been translated into Russian). In contrast, Abu Adel prefers to publish his works on Islam, Arabic grammar and Qur’an translation for a wider audience, in Russian.

Within the field of inter-Islamic polemics in Russia, one of the main criticisms levelled against Salafi and orientalist Qur’an translations relates to their lack of transparent recourse to clarificatory works of exegesis as a source for translation choices. Abu Adel’s translation adopts tafsīr in a very clear way and, as a result, the type of criticism his translation has received has shifted to a different level. The perceived quality of his translation is now determined by the ‘moral geography’ of the translator, in his case a Saudi version of Islam and thus usage of Salafi tafsīr. The geo-cultural influence of tafsīr now defines which tafsīr is authoritative and, therefore, which translation is more ‘correct’. In this context, Abu Adel’s use of al-Tafsīr al-Muyassar to underpin his Qur’an translation reflects a wider trend in the discursive polemics involved in Qur’an translation at the level of authorial self-assertion. Presently, the idea of tafsīr as providing an ‘authentic’ foundation that underpins translation choices as the criterion for a good translation applies generally in Russian Qur’an translations, be it an Ashari/Maturidi or Salafi translation, or even a translation produced within an academic setting.

The attribution of a singular meaning to a given word or phrase in translation due to reliance on a short ‘summary’ tafsīr inevitably results in loss of the polyvalence that was a mark of the premodern interpretive tradition. At the same time, it allows a translator to deliver unambiguous ‘normative’ renderings that make engagement with the scripture easier for the layman. Considering the post-Soviet context and the audience, Abu Adel’s provision of succinct commentaries in his translation is a way to avoid possible confusions and uncertainties, and thus can be seen as an important strategy for post-Soviet Qur’an translations.

Al-Tafsīr al-Muyassar is presented as a good interpretative foundation in this translation on the basis that it adheres to the Salafi trope of reading the Qur’an ‘in accordance with the beliefs of the first, righteous generations of believers’ i.e. al-salaf al-sāliḥ. There are a few more comprehensive tafsīr options available that could be considered as reliable and authoritative by Salafi communities, such as the ḥadīth-based Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿaẓīm of Ibn Kathīr, or the more contemporary Taysīr al-karīm al-raḥmān by al-Saʿdī. However, they would not easily serve the purpose of this translation, the primary aim of which is concise guidance. The question of religious certainty is approached from different epistemological stances in different Muslim communities: whereas for Sufis it is achieved through studying layers of rational knowledge and experience (for example through kashf, ‘unveiling’ of the knowledge of the heart), Salafis advocate for certainty based on scriptural sources. Thus, a Qur’an translation based on a concise, authoritative Saudi tafsīr composed ‘in accordance with the belief of the Salaf’ is a work that can, perhaps, bring its audience closer to what is considered to be an authentic reading of the Qur’an from a Salafi point of view, and is also one which empowers and democratizes the use of scripture. At the cost of polyvalence, we get a book of guidance that is accessible to a general post-Soviet readership which does not require additional input from the scholarly elite during one’s daily engagement with the Qur’an. It should also be noted that in order for Abu Adel to achieve his goal of producing a concise translation, even al-Muyassar had to be shortened and abridged in order to fit the format, and therefore Abu Adel does not follow its exact wording. However, Abu Adel sees his work neither as a perfect rendition that represents a final pinnacle in Qur’an translation, nor as a work that may fully satisfy an interested readership. Quite modestly, he presents this short tafsīr-based translation as a first step for beginners on their path to understanding the Qur’an.

When it comes to the text itself, it is noticeable that Abu Adel does not use Russian (or Christianised) ‘equivalents’ for the names of the Prophets or terms such as ‘God’ (Бог). These are all written as they are pronounced in Arabic. This, in itself, signifies how important the issue of authenticity is perceived to be, and how it is manifested in the style of this translation. When we look closely at specific features of the Salafi hermeneutic approach, Abu Adel’s translation consistently accords to the principles of imrār or tamrīr, terms which express the idea of amodality towards the anthropomorphic words used to describe God in the Qur’an, presenting them as they are without attempting to provide figurative interpretation (Evstatiev, 2021). Examples of this can be found in the verses mentioning God’s attributes, i.e. His ‘hand’ (yad), eyes (aʿyun) or ‘ascension to the throne’ (istawā ʿala l-ʿarsh) and so on. We can see how Abu Adel conforms to this approach to the text in his translation of Q 67:1 ‘Благословен [славен и преблаг] Тот, в руках Которого власть (над всем) и Который над всякой вещью мощен [всемогущ]’ (‘Blessed [glorious and righteous] is He who has Power in His hands (over everything) And who is powerful over everything [almighty]’), as well as in Q 54:14 and Q 32:4. At the same time, Abu Adel does not overburden his work by imposing complex Salafi theological theories on his translation. For instance, when discussing the oneness of God (tawhīd) mentioned in Surat Ikhlās (Q 112), most modern Salafi tafsīrs, including al-Muyassar, mention the differentiation of three categories within tawḥīd (tawḥīd al-rububiyya, ‘the Oneness of Lordship; tawḥīd al-ilāhiyya, ‘the Oneness of Godship’; and tawḥīd al-ʿibāda, ‘the Unity of Worship’). This differentiation is considered to be one of the important features of the Salafi creed. Nevertheless, Abu Adel simply writes: ‘Он – Аллах – один [нет у Него сотоварища]’ (‘He is God alone [without any partner]’).

The translation is accompanied by two types of interpolations presented within different types of brackets. Those enclosed within circular parenthesis represent additions made by the translator on the basis of his own assumptions about the syntax and structure of the Qur’anic Arabic, while square brackets denote interpretations and meanings taken from the aforementioned al-Muyassar. In some editions, the use of different colored fonts also helps to clearly differentiate between translation and tafsīr.

For quite some time, Abu Adel’s translation was overshadowed by another Russian Qur’an translation commonly associated with the Salafi trend, authored by Elmir Kuliev. However, in recent years, Abu Adel’s translation has won wider readership and recognition, because of its concise juxtaposition of direct translation and short tafsīr-based interpolations. Despite the fact that this translation demonstrates clear reverence for and esteem towards the authority of the Saudi version of Islam, it has not been published by the renowned KFCPQ, in contrast to that by Elmir Kuliev, and it is best described as an individual project published predominately by private publishing houses in Russia. Nevertheless, even without any institutional support, it is currently gaining in popularity, partly as a result of its availability on various apps, and its publication by well-known publishers in Russia such as HIKMA. It also has been promoted by the Association of Muslims of Ukraine (one of the few large Ukrainian Muslim associations), who have popularized it in Ukraine through the distribution of free Qur’an translations. Recently, a new edition has also been published in Moldova. The fact that this translation has become an international choice for publishers operating outside the borders of Russia is a compelling reason to see this translation as a successful rendition, the popularity of which will possibly grow in coming years.

Elvira Kulieva