The translator in this week’s post is very much a household name for readers of the Qur’an in English, but what are the roots of that popularity? And who is the man behind the name: Abdullah Yusuf Ali? It is commonly stated that Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s “The Holy Qur’an” has been printed more than any other in English, and is most sought after. A.R. Kidwai, in his bibliography of English translations, managed to identify over 200 editions of Yusuf Ali’s translation up to the year 2002. (NB: some are filed under earlier years than their actual publication.) “The Holy Qur-ān: English Translation & Commentary” was first published in Lahore between 1934 and 1937. Yusuf Ali himself released a corrected edition in 1938. However, he was not to witness changes made in later decades.

Aside from its inherent merits, the translation was boosted through its adoption by numerous publishing houses worldwide, most notably the King Fahd Complex in Saudi Arabia. We will look more closely at that later, but the key point for now is that Yusuf Ali was selected for wide distribution, often for free, by major vehicles of da’wah: another example being Ahmed Deedat’s (1918–2005) Islamic Propagation Centre International (South Africa). Although a translator’s background (especially theological affiliation) is often a deciding factor for Muslim readers, Abdullah Yusuf Ali seems to have occupied a neutral space among Qur’an translations, and himself sunk into the mists of time. As M.A. Sherif argues in his biography, “the Muslim world seems to have settled for an image of a quiet scholar with mystical leanings and left it at that, a gross injustice to a life of political involvement, prolific literary output and public service.”

Abdullah was born in Surat, in the Western Indian state of Gujarat, in 1872, to a family from the Dawudi Bohra branch of Shi’a Islam. Though it is sometimes claimed that he – or the whole family – became Sunnis, it may simply be the case that his views were broad enough to fit the intellectual landscape of his time, which was often cosmopolitan rather than sectarian. The Shah Jahan Mosque of Woking, of which Yusuf Ali was later a trustee, is illustrative of this phenomenon. The fact that his translation was promoted by the Saudis is another factor leading people to assume he was Sunni, but it should be kept in mind that the King Fahd Complex removed from his footnotes “thoughts not in conformity with the sound Islamic point of view.” By the same token, many of his original notes are uncharacteristic of a Shi’i writer.

The young Abdullah learned Arabic from his father, and was schooled in Bombay at the Anjuman-e-Islam (also attended by the likes of M. Ali Jinnah), and a missionary school of the Free Church of Scotland. He graduated from Bombay University and won a scholarship to study in the UK at St John’s College, Cambridge. After graduation, he secured a post with the elite Indian Civil Service, rose through its ranks, and oscillated between India and England until 1914. He made connections with major Muslim thinkers of the time, including Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), who would later seek out Yusuf Ali to lead the Islamia College in Lahore. It was in this city that he explains that local youth urged him to publish his ongoing work on the Qur’an “each Sīpāra [aka juz’] as it is ready” over three years.

The translation and commentary (over 6000 footnotes, 14 appendices, sura introductions, an index, and non-rhyming versified summaries running throughout) was received well in his lifetime by the general public, traditional scholars and the intellegentsia. Yusuf Ali continued to play a significant role in public life, and he left behind writings besides his Qur’an translation (see Sherif’s biography; he notes that his personal diaries, which he intended to preserve, were lost). However, his life took some tragic turns before he commenced the translation, and then up to his death in 1953. See this useful background on the Turkish TRT site (with special focus on his support for the British against the Ottomans).https://www.trtworld.com/…/how-the-british-empire…

In his introduction, Yusuf Ali outlines sources of exegesis, noting that he has referred to Ṭabarī, Zamakhsharī, Rāzī, Bayḍāwī, Ibn Kathīr and the Jalalayn, alongside Indian authors and translators. He makes a brief positive allusion to “the Modernist school in Egypt”. After criticising Orientalist translations, he describes earlier Muslim forays into the field. As we shall see, he sometimes references these works (e.g. Muhammad Ali as “M.M.A.” and Ghulam Sarwar as “H.G.S.”) in his footnotes. Yusuf Ali’s translation is noted for its literary quality and is more idiomatic than many. The language has sometimes been deemed archaic (e.g. use of “ye, thee, thou”) and updated in later editions. While it is the case that Yusuf Ali displays the influence of modernist thought, some criticism of his “pseudo-rationalism and apologia” (Kidwai) is overstated. We will consider one case, which also illustrates how his work was manipulated long after his death.

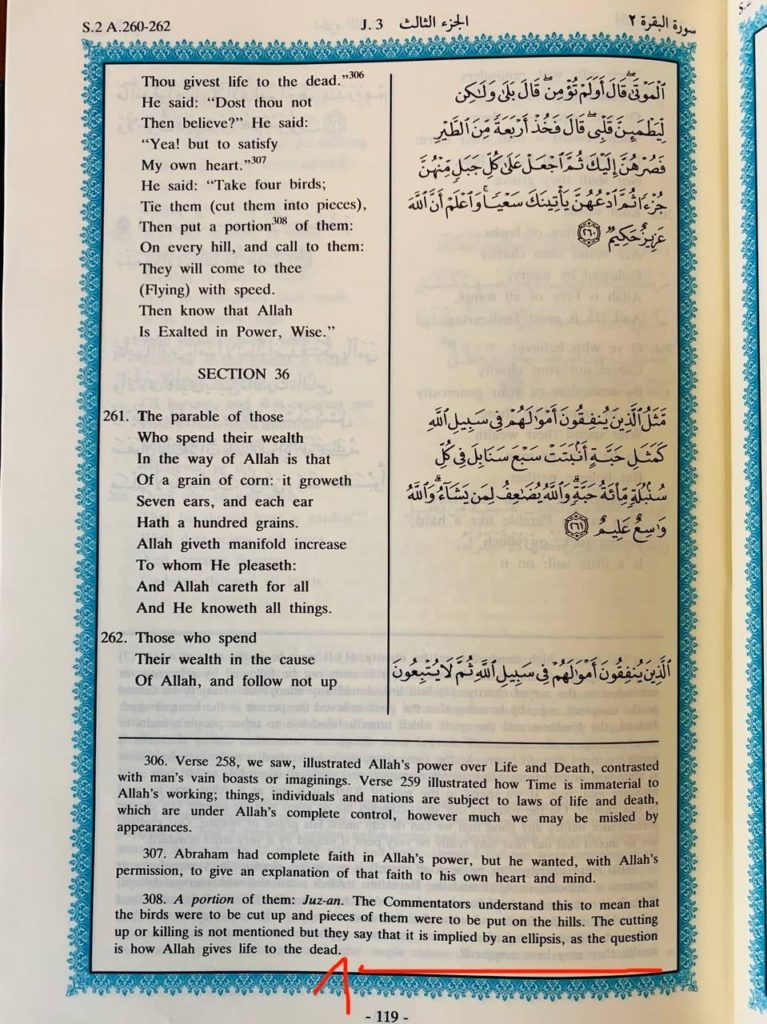

Q 2:260 describes Abraham’s request to be shown how God gives life to the dead. He is told that he should take four birds, place them on hills, then call them back. The vast majority of exegetes understood that the birds were to be killed and chopped up before placing them; so this is a resurrection event demonstrating God’s ability. However, Rāzī and others record an alternative view in which the birds aren’t chopped. Instead, this verse describes a mental demonstration: if you train the birds to recognise you, they will rush back upon your call; and this illustrates how all of creation will respond to the Creator on Judgement Day. Yusuf Ali explains in his footnote that he is persuaded of this view after encountering it, not with Rāzī (from Abū Muslim al-Iṣfahānī), but with Muhammad Ali and Ghulam Sarwar. As I argue in a forthcoming open access paper (Sohaib Saeed, “Fights and Flights”, Journal of Qur’anic Studies 24.1), this reading is far more persuasive on linguistic and other grounds than many exegetes gave it credit.

What concerns us now is the afterlife of this translation and footnote. The first change occurs with the Saudi (King Fahd Complex) edition of 1987, which adapted Yusuf Ali’s work freely and did not name him on the cover.* The KFC edition changes “Tame them to turn to thee; put a portion of them on every hill” to “Tie them (cut them into pieces), then put a portion of them on every hill”. They also truncate the footnote to remove Yusuf Ali’s disagreement with “the received Commentators”. It should be noted that the “tie” meaning, while attested, is also unusual. Later editions by other publishers have tended to restore Yusuf Ali’s own rendering, but sometimes they also truncate the footnote or remove it (and others) altogether. However, there is another twist in the tale! If you search for Yusuf Ali’s translation online nowadays, you will likely encounter something else altogether. For example, Quran.com presently has:

𝘞𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘈𝘣𝘳𝘢𝘩𝘢𝘮 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥: “𝘚𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘮𝘦, 𝘓𝘰𝘳𝘥, 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘥,” 𝘏𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘱𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘥: “𝘏𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘯𝘰 𝘧𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘩?” 𝘏𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥 “𝘠𝘦𝘴, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘴𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘮𝘺 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵.” 𝘈𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘩 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥, “𝘛𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘪𝘳𝘥𝘴, 𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘸 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮 𝘵𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘪𝘳 𝘣𝘰𝘥𝘪𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘱𝘪𝘦𝘤𝘦𝘴. 𝘚𝘤𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮 𝘰𝘷𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘯-𝘵𝘰𝘱𝘴, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮 𝘣𝘢𝘤𝘬. 𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘺 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘴𝘸𝘪𝘧𝘵𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶. 𝘒𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘈𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘩 𝘪𝘴 𝘔𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘺, 𝘞𝘪𝘴𝘦.”

Even more confusingly, this alternative translation is listed on the IslamAwakened website (and subsequently in an academic paper) as being the Saudi version. In reality, it does not appear in any print edition I have seen. Its origin appears to be a PDF that was distributed online after some changes were made (how many or by whom, we don’t know): and the translation of 2:260 was replaced by something extremely similar to that of N.J. Dawood (1927–2014). This story of tampering (or “correcting”) has played out in translations of this verse and others, as it has in Arabic commentaries and editions. It calls for attention to the provenance of Qur’an translations, particularly in the digital age.

Sohaib Saeed

* This approach was condemned by the renowned Muhammad Hamidullah (1908–2002) in an open letter to the Saudi king. His own French translation would receive the same treatment in 1990, much to Hamidullah’s chagrin.