Qur’an translation as propaganda: war alliances and nation-building (2/3)

In the period between the two world wars, Nejmi Sagib Bodamialisade (1897–1964), a Muslim in Cyprus, an oft-forgotten corner of the British Empire, started translating the Qur’an into English verse in order to gain British support for Muslim Cypriot interests.

His translations of segments of the Qur’an, published in short booklets, are among the quirkiest examples of Qur’an translation, if the term “translation” is even applicable to them. Nejmi Sagib’s self-chosen name is derived from the Qur’an, specifically from the phrase al-najm al-thāqib (“the piercing star”) in Q 86:3. He was, at the very least, an eccentric; less charitable scholars suspect that he may have been mentally unstable. His Qur’an translations are nevertheless more than a mere curiosity. They are an emblematic part of the history of Muslims in British Cyprus, and they tell us much about the changing fates and political orientations of Turkish Cypriots between the 1920s and 1950s.

Consider this text sample:

READ by the Name of ALLAH, the Almighty Author,

Read, learn, teach, publish all the world over;

Read by the Help of your LORD, who created Man,

Gave senses and reason, taught the uses of Pen;

To learn and teach is part of Moslems’ Worship,

Fulfil your highest, brightest duty, don’t slip;

Yea, teach Islam, the True Religion for all,

Save Mankind from darkness, error and fall;

Read, learn, teach Gouran, the Sacred Treasure

Of Light Devine for all in the world everywhere;

GOD’s greatest Gift is ability to learn,

All Knowledge is Holy, don’t neglect, don’t spurn;

All riches and earthly glories are transient, vain,

Prefer Knowledge to every kind of wealth and renown;

The highest Glory is Justice, Truth and Devotion,

The highest Renown is the highest Civilisation;

Obey ALLAH, you shall return to HIM,

Be not envious, idle, ignorant and dim;

Those who prevent from worship and learning shall

Be punished with everlasting Fire and Hell;

The Light of Knowledge is the greatest power,

Man can by it rule all the forces of Nature,

Defeat his foes, supply his needs anywhere,

Advancement, success and every perfection,

Is based upon Knowledge and Education;

Fight Ignorance: Source of slavery and Evil,

The Moslems must be saved and enlightened all!

O Nations, know and obey ALLAH your Preserver,

Almighty, All-Wise, Eternal and Knowledge-Giver.

This is just about recognisable as a very idiosyncratic take on Q 96:1–4, which many Muslims consider to be the first divine revelation to Muḥammad:

اقْرَأْ بِاسْمِ رَبِّكَ الَّذِي خَلَقَ

خَلَقَ الْإِنسَانَ مِنْ عَلَقٍ

اقْرَأْ وَرَبُّكَ الْأَكْرَمُ

الَّذِي عَلَّمَ بِالْقَلَمِ

and which has been translated by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem as:

“Read! In the name of your Lord who created:

He created man from a clinging form.

Read! Your Lord is the most Bountiful One,

who taught by [means of] the pen.”

Nejmi Sagib’s verbose rendering not only reflects his conviction that Islam was meant as guidance to mankind as a whole, but also his desire to present Islam as a religion of learning, education and “civilization.” These concepts were of the highest importance to him and were inextricably linked to a political agenda that can only be understood in the context of Turkish Cypriot politics in the interwar period.

Cyprus had been under Ottoman rule from 1571 to 1878, when the Ottomans ceded its administration, but not the territory itself, to Great Britain in exchange for protection against Russian attacks. The British later unilaterally occupied the island in 1914 as a response to the Ottoman entry into the First World War. In 1925, Cyprus became a Crown colony after the Turkish Republic, the legal successor to the Ottoman Empire, had ceded its claim to the island.

At this point, the island had a population of 330,000, the majority of whom were Greek while a little less than 20% were Muslim, most of them Turkish-speaking but also bilingual (or even trilingual). It was during the interwar period, under British rule, that the Muslims of Cyprus became a community of “Turkish Cypriots” with a distinct ethno-national identity. This was due to several factors.

First, the British pursued a “divide and rule” policy and tried to play the Turks against the Greeks. The Turks were largely members of the urban middle class, and many of them worked in the administration. The British relied on them to counter Greek political aspirations. The Greek and Turkish education sectors were completely separate from each other, and only the Turkish schools were administered by the British.

The aforementioned Greek political aspirations were the second important factor. During the interwar period, there was a strong movement among Greek Cypriots towards unification with Greece (Enosis). The Turkish Cypriots considered this an existential threat, having witnessed, among other things, the forcible expulsion of the Muslims of Crete after its unification with Greece. Most Turkish Cypriots therefore were loyal to the British whom they saw as their main protector against the Enosis.

Third, the emergence of print capitalism and mass education strongly contributed to the formation of political identities on Cyprus. And fourth, the Turkish Cypriots were keenly aware of Kemalism and its impact on the Turkish Republic. While Kemalism was a source of internal debates, it had a deep impact on the development of the Turkish Cypriot community. By and large, Cypriot Muslims adopted the Turkish language reforms of the 1930s, which meant that publications from the Turkish Republic were easily accessible to them and textbooks from Turkey could be incorporated into Turkish Cypriot curricula.

These factors, working together, led to an accelerated process of identity formation among Turkish Cypriots. While, during the First World War, being perceived as Turkish had been regarded as a source of embarrassment, this attitude was slowly replaced with one of pride in being Turkish, but with a distinctively Cypriot flavour that, for many Turkish Cypriots, included an affinity to British culture, and this was especially so for Nejmi Sagib.

Born as Mahmut Aziz, he seems to have renamed himself at an early age to “Nejmi Sagib”, or in later Turkish Spelling Necmi Sagıp, a religiously inspired and also rather grandiose choice that is consistent with the outstanding role he tended to attribute to himself. There are conflicting reports about many episodes in his life, but it seems certain that he studied at Oxford for a year or two until he left Britain without a degree in 1921. According to one account, he was expelled from the country for having written poems with communist tendencies in support of Welsh coal miners who were on strike, but, according to another, this happened because he had offended the then Prime Minister Lloyd George by asking for his daughter’s hand in marriage.

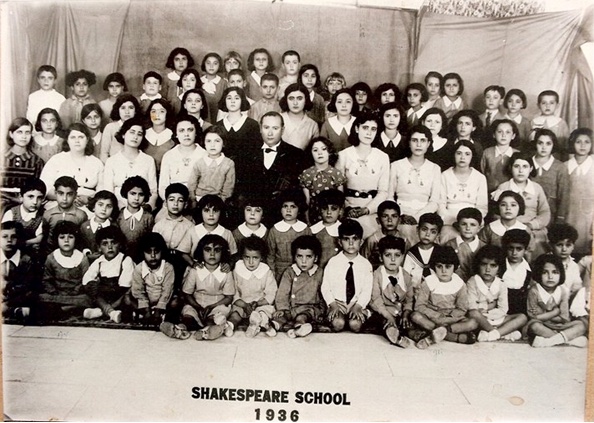

When he returned to Cyprus, he was one of few Cypriots who were fluent in English. This led him to eventually open an English school, the “Shakespeare School” in Nikosia, which at first only provided evening classes then later, in around 1933, supplemented this with daytime teaching. The school proved successful. Nejmi Sagib, a firm believer in the importance of educating girls, taught boys and girls together and the number of female students seems to have been higher than that of boys. (The picture of him with his students can be found on https://cyprusscene.com/2016/09/08/frozen-cypriots-my-mum-at-shakespeare-school-with-necmi-sagip-bodamyalizade/.)

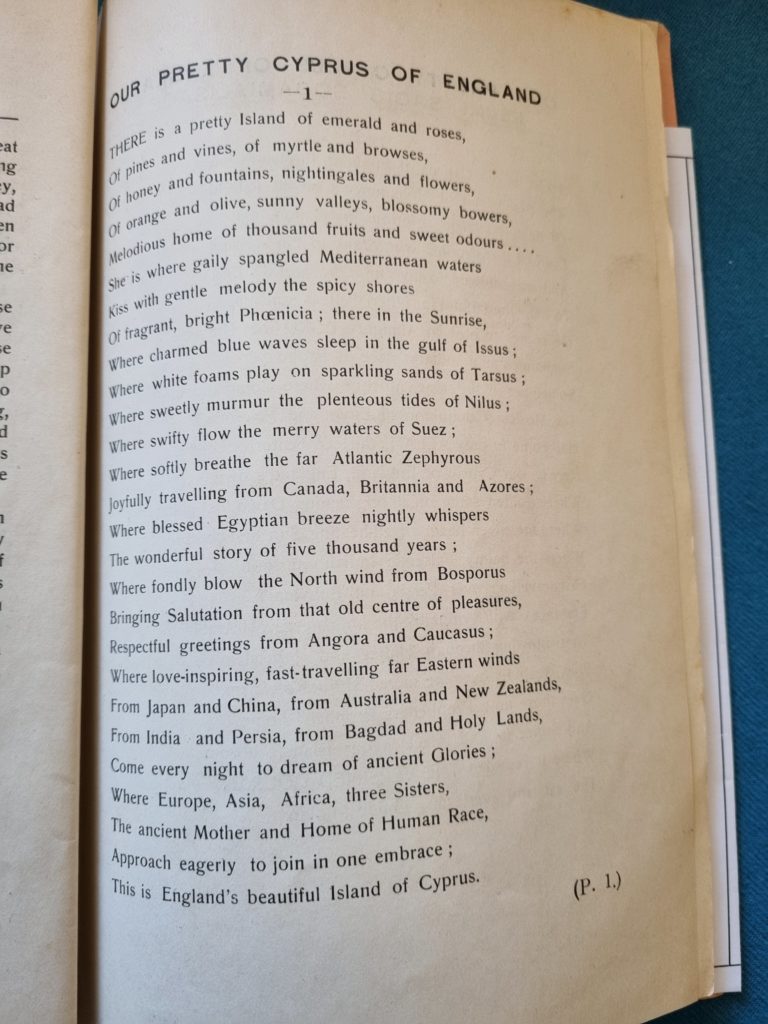

Like many subjects of the British Empire, Nejmi Sagib had been raised to consider Shakespeare’s writings the pinnacle of world literature, a fact that is obvious from the name of his school, as well as his activity as a translator of poetry from English to Turkish and vice versa. His translations from Turkish were evidently meant to convince British readers of the high civilizational standard of Turks. He also wrote essays and lyrical poems that extolled Britain’s rule over Cyprus. In 1929, he published a collection of these writings to celebrate the fifty-year anniversary of British rule under the telling title “Sacred Trumpet,” which reflects the sense of having been tasked with a divine mission which permeates his entire oeuvre. His poem “Our Pretty Cyprus of England” contains the following lines, which describe his perspective on the Muslim Cypriots and perfectly summarize his agenda during the 1920s and 1930s:

To thee, England, they are loyal unto death,

They are entrusted to thy guidance and thy faith

and now in agony are drawing their last breath.

To thee, England, they have been loyal, and shall, for ever;

What carest thou for a few bribed, blind traitor

Of unknown origin and doubtful religion

Bought and sold for a handful of gold or silver?

Look at the Thousands, Faithful unto death,

Surrounded by an enemy beyond their strength,

By an enemy artful, cunning and treacherous,

Strongly supported, and five times their numbers,

Thy Moslems are being crushed in the coils of these adders,

They are being choked by poisoned fangs of traitors,

Their blood is suck, their life poisoned, and stained is their honour!

THOU canst save them, England, at one effort, no more,

They are virtuous, of good heart and good nature,

They have excellent talent for education and culture,

Stretch they gracious hand and be their saviour

Be the saviour of these Moslems of Cyprus, thine own.

At the core of Nejmi Sagib’s activity as an author and translator were his Qur’an translations that he self-published in cheap, semi-professional softcover booklets, which he apparently also used as textbooks in his school. All of them were in verse, which was obviously the highest form of literary expression in Nejmi Sagib’s view, as well as the only way to bring across the beauty of the source text. He was unconcerned with, and possibly unaware of, dogmatic misgivings about translating the Qur’an as poetry, nor does he seem to have encountered any substantial criticism for it. The sequence of these translations as they were published from 1925 to 1959 shows a clear development in his religious interests and political orientation.

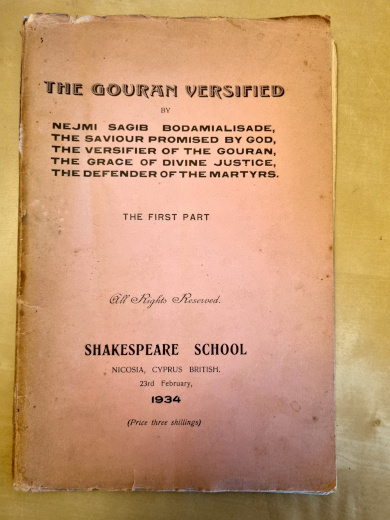

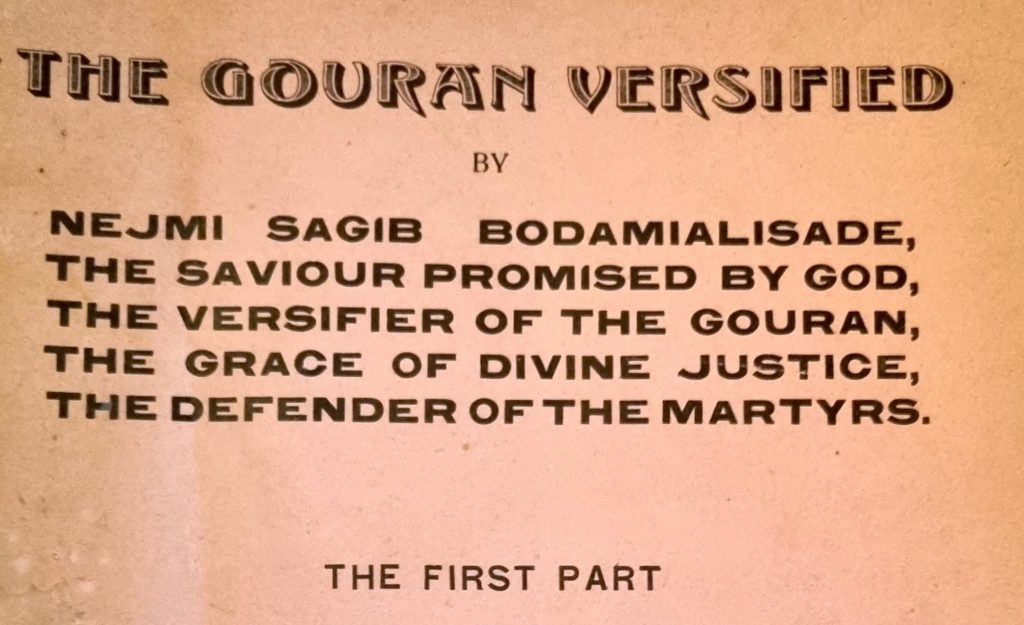

The first of his translated segments of the Qur’an was apparently published in 1925 under the unassuming title “The Koran. A New Version”. In 1934, Nejmi Sagib then published all the English translations he had previously produced under the title “The Gouran Versified. The First Part” and garnished the title page with a number of epithets according to which he was

“the saviour promised by God,

the versifier of the Gouran,

the grace of divine justice,

the defender of the martyrs”.

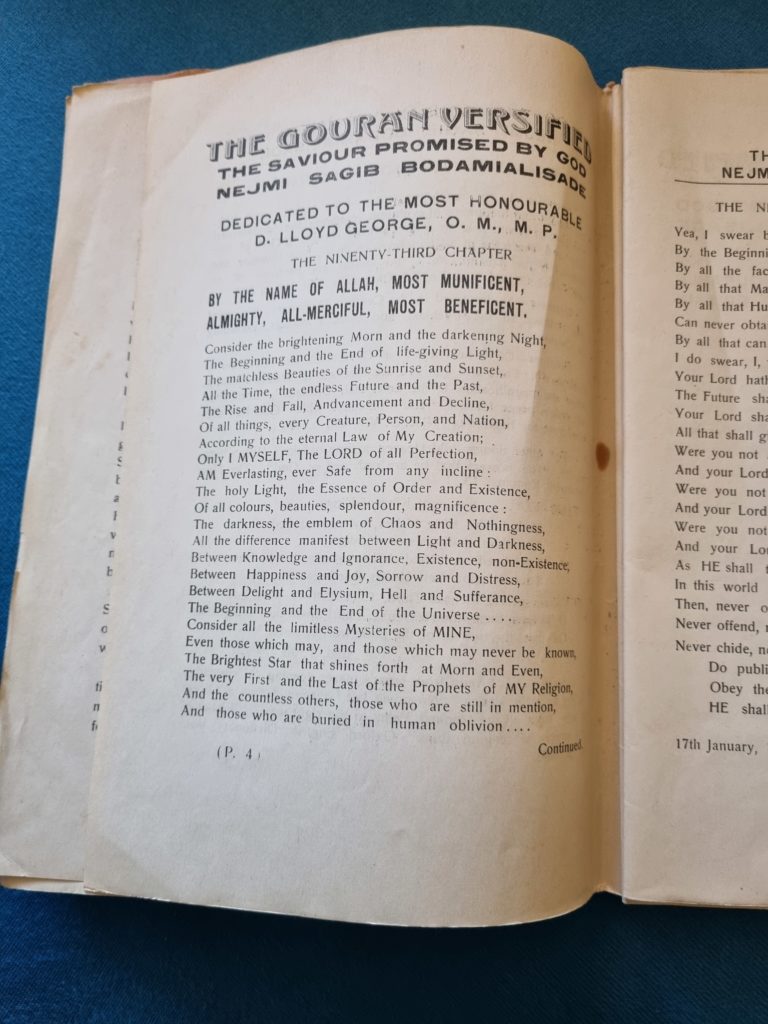

The book contains a motley collection of material that included letters, lists of graduates of the Shakespeare School, an essay on “Great Britain and the Moslems”, a translation of a Turkish poem and so forth, but at its core are 22 pages of Nejmi Sagib’s take on various suras and verses. They are taken from various parts of the Qur’an but mostly from the first two suras and the short suras at the end. The translations are consistently longer than the original, sometimes moderately so (one page for Q 23:1-11) and sometimes excessively so (five pages for Q 72:1-5).

Still, at least in the early stages of Nejmi Sagib’s activity, the correlation with the source text is discernible. It is also occasionally possible to perceive that Nejmi Sagib drew either on a work of tafsīr,or possibly an existing translation (or even based his writings on such an existing work, rather than translating the Arabic Qur’an itself). For example, he rendered the disjointed letters in Q 2:1 (alif lām mīm) as “I am Allah the Omniscient”, which is an interpretation found in a number of qur’anic commentaries and also, for example, in Muhammad Ali’s English Qur’an translation published in 1917.

He was not overly concerned with precision, though. Not only did he add to the contents of the source text, he also left out details that he might have thought irrelevant or unsuited to the message he wanted to convey. For example, Q 23:1–11 describes the believers who will attain Paradise as being those who are humble in prayer, avoid idle talk, guard their chastity, except towards their spouses and slaves, are faithful to their trusts and uphold their prayers. Nejmi Sagib apparently considered this list too short and added some more virtues: the learning and teaching of arts, knowledge and science; obedience to God’s orders; the avoidance of wine and gambling; paying taxes and not desiring unlawful wealth; striving for Islam; and defending one’s home. He also edited the reference to permissible intercourse with slaves out of the text and reduced the relevant segment to merely saying that true believers “approach none but their lawfully married mate”. His concluding lines, furthermore, come across as rather un-qur’anic:

These Rules Unalterable and Divine,

Shall be Foundations of real Civilization.

A concern with portraying Islam as civilized and highlighting the importance of learning and teaching permeates his work, but the most central and endlessly repeated message, from his first translation in the mid 1920s to his last in the early 1960s, focusses on God, whose name is always written in capital letters. GOD is the creator as well as the omniscient, all-powerful lord of the universe, in this world and the hereafter, and mankind will only find salvation through worshipping Him. Nejmi Sagib sees this as a universal message to mankind and presents it with missionary zeal. In his version of Q 2:23-24, he writes:

GOURAN is the Word of God, the Light of the World,

The Dread of the Evil, and the Guide of the Good;

GOURAN is Everlasting and Eternal,

Part of MY Omniscience, of MY Wisdom and Soul,

Nothing higher than the GOURAN, IT is all in all,

The Light Divine that shall shine from Pole to Pole;

O Nations fallen, O peoples in disaster,

Sincerely follow MY Book, and do not despair,

You shall rise, you shall conquer, you shall prosper…

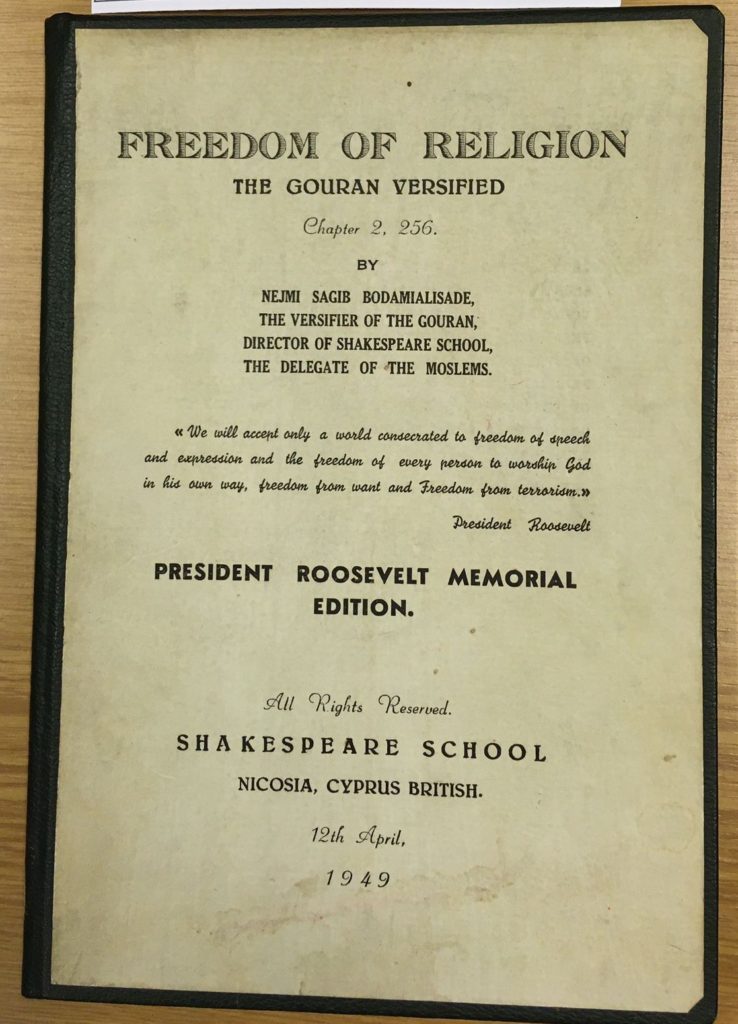

The message of God as creator of the universe is taken up in a sequel, first published in 1944, that is entitled “God and the Universe”. Nejmi Sagib has by this time considerably toned down the descriptors of himself on the cover page: he now calls himself “the Versifier of Gouran, Director of the Shakespeare School, the Delegate of the Moslems.” The latter title is one he awarded himself, following a period during which he took to riding his bike across Nikosia and collecting signatures from Turkish Cypriots for a petition against independence from Britain, which he then presented to the British administration.

The entire booklet of “God and the Universe,” comprising sixteen pages, is devoted to just two verses, Q 3:26–27. The dedication is an excerpt from the text:

In the darkest period of human history,

Thou hast sent this book to be the Guide and Glory;

To lead all men to Truth and Happiness,

To lead all nations to Brotherhood and Peace.

In the face of a catastrophic World War, Nejmi Sagib emphasizes in this version of the Qur’an God’s omnipotence, as well as His capacity to give power and sovereignty whom He wills, and to take them from whom He wills: “The deepest darkness Thou turnest into Light.” This message of hope and trust in God then shifts to consideration of the miracles of God’s creation as they become evident in the laws of nature, taking on a note of amazement at scientific and technological progress that had not been entirely absent from the previous book but which is explored more fully here:

“Thou storest wonderful force in the tiniest atom;

Amazing vitality in the weakest germ […]

Thou didst ordain each natural law and rule

By which we keep heat and light yet under control,

We make use of them for every purpose and need,

To move our motors and machines, to cook our food.

Thou hast created so many means and sources,

Most wonderful contrivances and forces …”

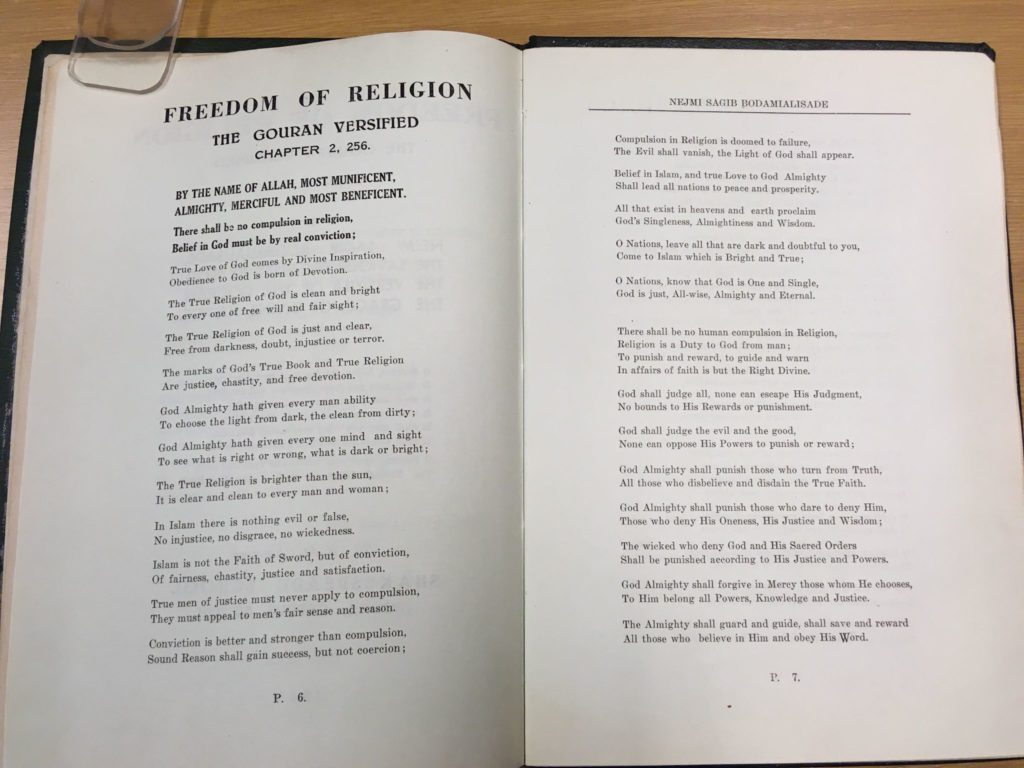

The image of God as the creator of the awe-inspiring laws of nature was fashionable in its time and used by Nejmi Sagib to portray Muslims as modern, progressive and therefore worthy of patronage and protection. That theme was continued in his subsequent book, which was published in 1949 and is entitled “Freedom of Religion” and labelled as a “President Roosevelt memorial edition”, with a quotation by Roosevelt on the need for freedom on the cover. The bulk of this volume is devoted to one single verse, Q 2:256, read as a statement on freedom of religion, to which Nejmi Sagib devotes no less than 21 pages.

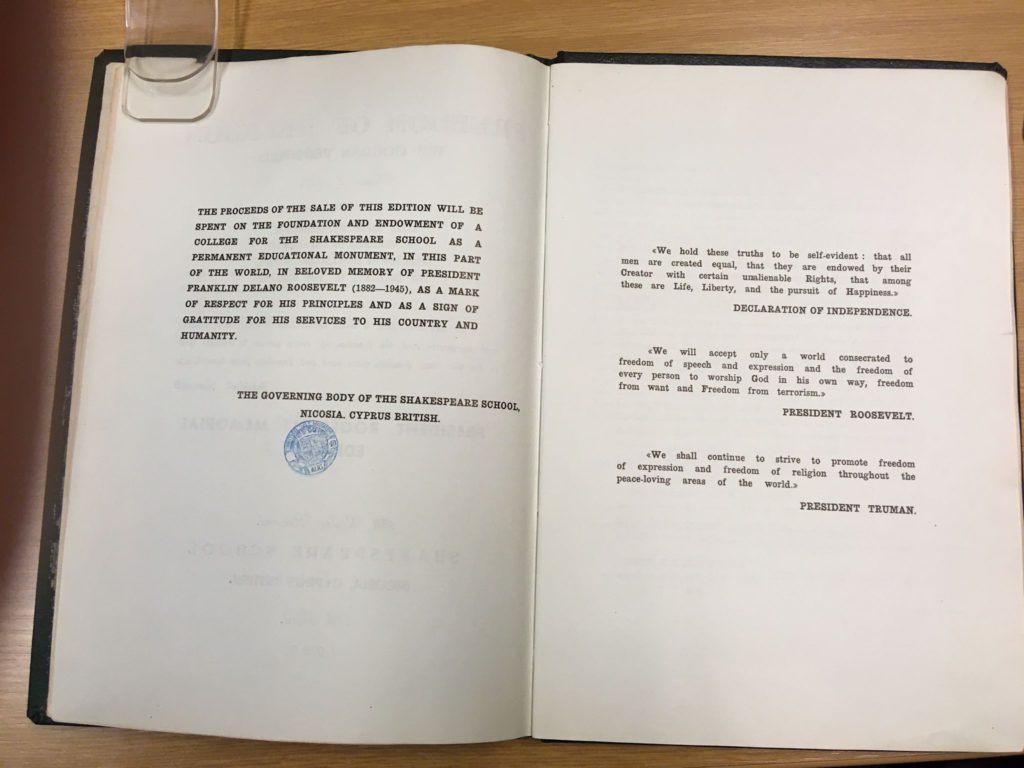

It is clear from a remark on the inside cover that Sagib tried to raise funds for his school with this publication, selling it “as a permanent educational monument to Roosevelt”. He was in dire need of funding by this time because the Shakespeare School had lost the unique position it had had in the 1930s and was in competition with many other schools, to which it was constantly losing students and income (it eventually had to close in 1952).

The book starts with quotations from the American Declaration of Independence as well as speeches by Roosevelt and Truman. This reflects a fundamental change in political orientation: it is now the United States, rather than Britain, that Nejmi Sagib appeals to for protection. After WWII, the independence of Cyprus, just like the issue of decolonization in general, was increasingly framed as an international goal to be achieved under the umbrella of the United Nations and with the help of one of the world superpowers, rather than the colonial powers themselves. Since the independence of Cyprus was now a likely event, the new political goal for Nejmi Sagib seems to have been an independent state with strong guarantees for the Turkish Cypriot minority.

In accordance with this new orientation, he started translating his English verse into Turkish for Turkish Cypriot newspapers, for example İstiklal (1949, 1950) and Nacak (1961). İstiklal announced in 1949: “Necmi Sagib Bodamialisade, the Delegate of Muslims, who translated the Qur’an into English in verse to show its true greatness and height, and called all the nations of the world to Islam, is busy translating the Qur’an into Turkish in order to convey the true meaning of the word of God to the Turkish nation. We consider it a religious and national duty to present the sura iqraʾ [Q 96] you find on this page to our readers. We proudly announce to our readers that we will try to publish a piece of this work every Friday.” The newspaper was short-lived, though, and Nejmi Sagib had to find other venues for publication. In 1959, he published a collection of his Turkish and some English Qur’an translations under the title “Manzum Kur’an,” now labelled as “translation and tafsīr”) (tercüme ve tefsir). This allegedly became a textbook for religious education in Turkish primary schools on Cyprus, which gained independence in 1960. By this point, the Turkish Cypriots were a community with a distinct ethno-national identity and strong ties to the Turkish Republic.

Nejmi Sagib’s attempt to keep up with this development and connect to it by switching to the use of Turkish was not very successful since he was increasingly out of touch with social and political developments. His good command of English, which had once been his biggest asset, had lost first its uniqueness and then its relevance. After independence, he could not assume a teaching post because he had never obtained a degree. Poetry, be it English or Turkish, was far from most Turkish Cypriots’ minds during the political crises and divisions that shook up the country after independence, and Nejmi Sagib’s approach of calling to Islam as the pathway to security and salvation appeared quite outdated to most of them. Nejmi Sagib spent the last years of his life in poverty and died in 1964 in social isolation.

His Qur’an translations in verse were soon all but forgotten, and they are today hard to obtain (our heartfelt thanks to Annabel Gallop for helping with this!). Looking at them from today’s perspective, it is easy to dismiss them as inexpert and somewhat laughable doggerel verse. However, they also show us a writer whose upbringing in the British Empire had given him a lasting passion for poetry, and who used this art form – in a language that was probably his third – to express his deep and unshakeable faith in God.

These are the last verses from his pen that we could find, published in 1961 in the newspaper Nacak as part of a medley of Qur’anic verses:

ALLAH’ın Sevgisine,

ALLAH’ın Merhametine,

ALLAH’ın Kudretine

GÜVENİNİZ.

In GOD’s Love,

in GOD’s Mercy,

in GOD’s Might

[shall be] YOUR TRUST.

Johanna Pink

My heartfelt thanks go to Béatrice Hendrich for her suggestions and references!