‘De Korte Hoofdstukken van de Koran’ (2002) is a translation and commentary of short Qur’anic verses by a Dutch Indonesianist and Islamologue, Karel Steenbrink, who built lasting personal relationships with many Indonesian Muslim scholars in both the Netherlands and Indonesia. At a time when many studies of Islamology emerging from Western universities focused their attention on the study of Muslims in the Arab world, Karel Adrian Steenbrink (1942–2021) decided to study Islam in Indonesia, focusing in particular on the ways Indonesian Muslims perceive the Qur’an as playing a part in their daily lives. His other publications on the Qur’an include ‘Adam Redivivus: Elaborations of The Adam Saga with Special Reference to Indonesian Literary Tradition’ (1998), ‘The Jesus Verses of the Qur’an’ (2006) and ‘Een Kleine Koran: Praktische Hulp bij het Lezen van de Koran aan de Hand van de Tweede Soera’ (‘A Brief Qur’an: A Practical Guide to Reading the Qur’an Using the Second Surah’, 2011).

Born into a religious family, Steenbrink pursued Arabic and Islamic studies at a Catholic seminary and continued his study of religion at Radboud University in Nijmegen. Influenced by his two professors there, Prof. Jean Houben (1904–1973), a pastor and Arabic language expert who had the ability to read the Qur’an well and beautifully, and Prof. Arnulf Camps (1925–2006), a professor of missiology specializing in the study of Christian and Islamic relations who conducted field studies rather than studying religious texts, Steenbrink decided to study the Qur’an using an approach rooted in empirical experience. He first conducted research on Indonesian modern reformist interpretations of the Qur’an such as those by Hamka, Hasby ash-Shiddiqy and Arifin Abbas, but the absence of identifiable interpretive communities made it difficult for him to obtain data during his stay in Bandung. He then turned his focus to pesantrens (Islamic boarding schools), and chose a modern pesantren in East Java, PesantrenGontor, for his fieldwork. His dissertation did not specifically focus on the study of the Qur’an, but his experience of living there for three months, during which he directly observed the meaning and position of the Qur’an for Muslims in their daily lives.

His experience of mondok (the Indonesian term for living and studying in a pesantren) and observing how his fellow students related to the Qur’an clearly influenced his decision to write ‘De Korte hoofdstukken van de Koran,’ a translation which is written primarily for non-Muslim Dutch readers who do not have access to the original language of the Qur’an. In the Preface he explains that the Qur’an was revealed as a message from God to humanity, and was used as a means to address God in return, especially through the short surahs that are widely read during prayer. That, he states, is the reason why the Qur’an is divided into 30 juzʾ; as the month of Ramadan generally consists of 30 days, which means that Muslims can read (tadarus) one juzʾ every night and complete it within the holy month. For him, the primary access to the text of the Qur’an for most Muslims lies in their practice of the five daily prayers (ṣalāt), during which the short surahs of the Qur’an are frequently used as prayer texts.

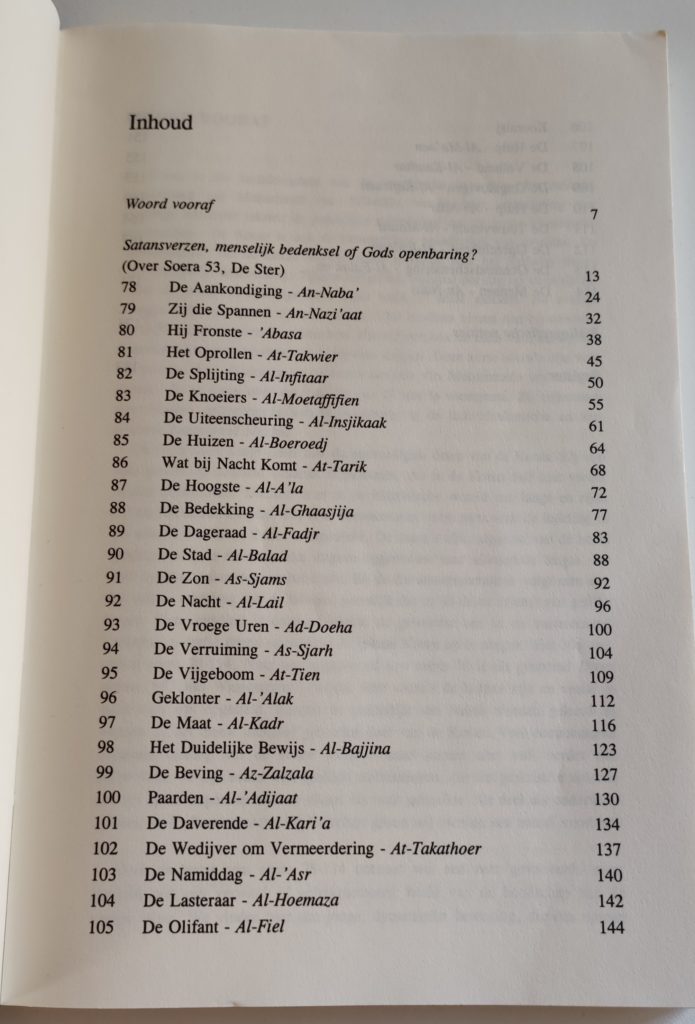

Interestingly, although Steenbrinks’ translation ostensibly sets out to provide readers with a translation of the short surahs at the end of the musḥaf known as the juzʾʿāmma, it starts (for reasons that will be addressed below) with Sūrat al-Najm, the fifty-third surah of the Qur’an. Most of the short surahs (from Surah 78 to the last surah, 114) presented in ‘De Korte’ were translated by Steenbrink himself, and these are indicated by the phrase ‘eigen vertaling’, while others are taken from pre-existing Dutch Qur’an translations, such as those by Sofjan Siregar, Kramers, F. Leemhuis, Soedewo and Rabwah Ahmadiyah. When it comes to commentary on the text, Steenbrink relies on interpretations from both Islamic and Western traditions. The Islamic sources he refers to comprise both classical and modern works, including the ḥadīth compilation of al-Bukhārī, and the tafsīrs of al-Rāzī, Muḥammad ʿAbduh and Fazlur Rahman, as well as Indonesian commentaries of the Qur’an, such as those by A. Hasan, Hamka and Quraish Shihab. The Western academic figures he refers to include John Wansborough, W.C. Smith and Annemarie Schimmel.

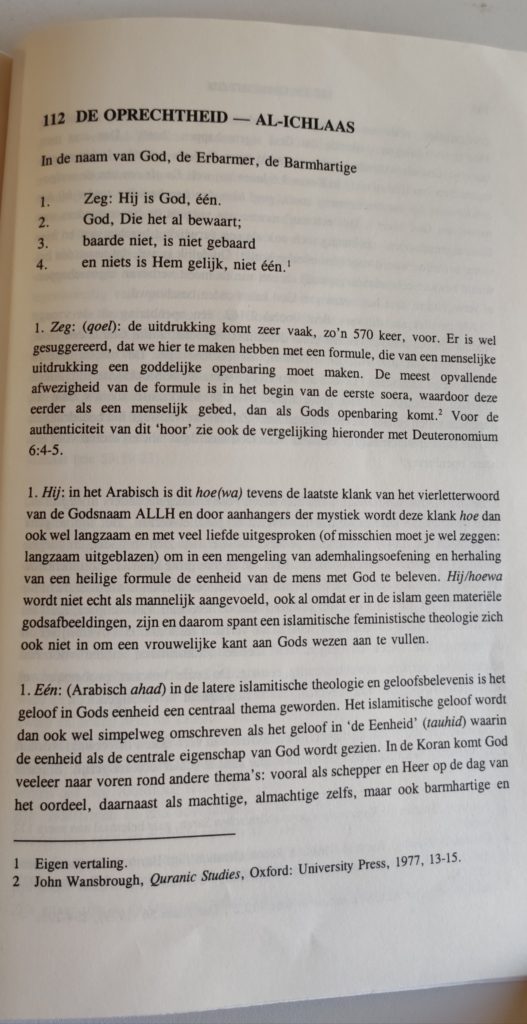

To show how Steenbrink differs from other Dutch translators of the Qur’an, I will quote his text of Sūrat al-Ikhlās, which he translates as follows:

In the naam van God, de Erbaner, de Barmhartige

- Zeg: Hij is God, één,

- God, Die het al bewaart

- Baarde niet, is niet gebaard

- En niet is Hem gelikj, niet één,

There are some significant differences in Steenbrinks’s translation of this surah and those found in other Dutch translations of the Qur’an. For example, the word احد in the translations of Siregar, Leemhuis, Verhoef and Abou Ismail is translated as ‘en einige’, which means ‘the only one,’ while Steenbrink interprets it as ‘één’ or ‘one.’ Then, the third verse of the chapter لم يلد ولم يولد is interpreted by Siregar, Leemhuis, Verhoef and Abou Ismail as ‘verwekte niet en Hij wird niet verwekt,’ which means ‘did not beget and is not begotten,’ whereas Steenbrink chose to render it into Dutch as ‘baarde niets, is niet gebaard,’ which means ‘gave birth to nothing, has not been born.’ Steenbrink also differs in translating the name of the surah, al-Ikhlās, as ‘de oprechetheid’ which means ‘sincerity,’ in contrast to Verhoef’s ‘ware gelof,’ or ‘true faith,’ and Leemhuis’ ‘Toewijding,’ or ‘commitment.’ In his commentary, Steenbrink explains that this (Meccan) surah is not directed against the Christians, since polemics against Christians did not figure in the Qur’an during the Meccan period, but rather against the so-called ‘daughters of God,’ the goddesses al-Lāt, Manāt and al-ʿUzza. This is in line with his response to the kyai (religious leader) of Gontor Pesantren, who asked his opinion about Sūrat al-Ikhlās, known as the surah about the oneness of God,when Steenbrink asked to join the five daily prayers at the pesantren, a request that surprised the kyai. Steenbrink explained that, as a Catholic, he believed that God is One and Jesus is not the son of God in the biological sense. He was then allowed to pray after the kyai reminded him to perform wudlu (Ar. wuḍūʾ, ‘ablution’) first.

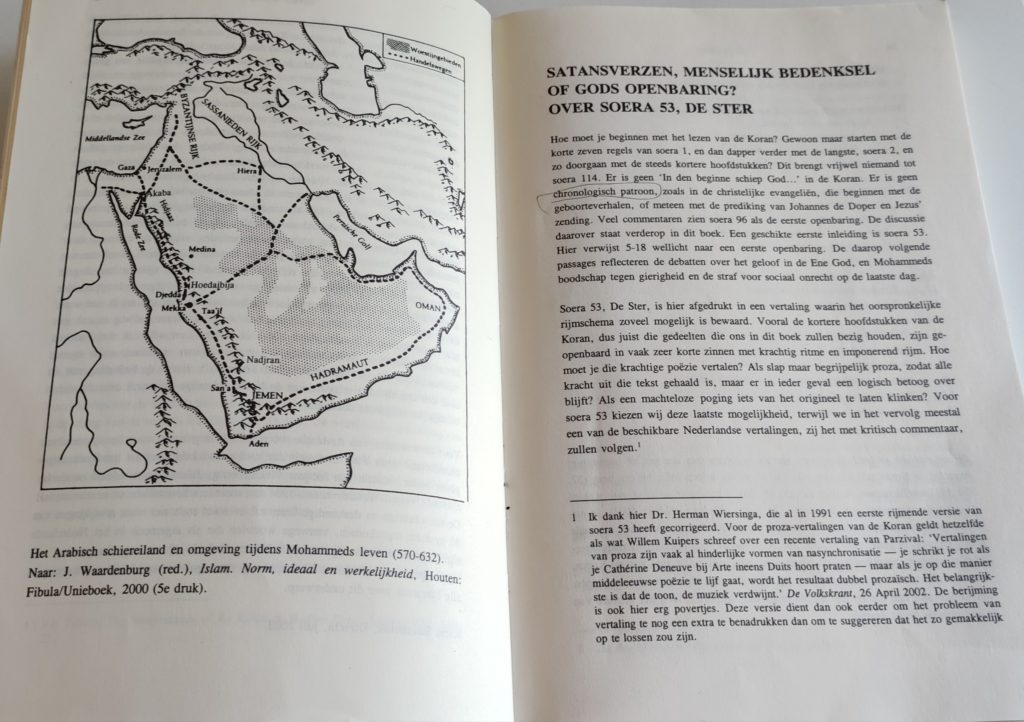

In his Introduction to his translation, Steenbrink compares the Qur’an with his own religious tradition, the Christian Gospel. Whereas the Gospel is organized chronologically, with birth stories about or discourses from Jesus or John the Baptist, the Qur’an, he says, is organized in different way. It begins with al-Fātiḥah and continues with the longest surah, al-Baqarah, after which the surahs following in order of decreasing length. He clarifies that Sūrat al-ʿAlaq is believed to be the first surah revealed but has been placed as the ninety-sixth in the order of the Qur’an, while Sūrat al-Najm, the fifty-third surah (especially verse 5 to 18), which contains an explanation of the revelation of Surah 96, was actually revealed after Sūrat al-Ikhlās. Steenbrink goes on to say that Sūrat al-Najm is not part of the juzʾʿāmma, the section of the Qur’an that he chose to translate in ‘De Korte Hoofdstukken’, but that for Steenbrink it was important to include it so that readers can get an idea of the beauty of Qur’anic language and style, and the poeticity of its rhythm.

Karel Steenbrink was known for his emphatic understanding of Islam and his translation ‘De Kortehoofdstukken van de Koran’ confirms this. Sahiron Syamsuddin, an Indonesian expert on Qur’anic hermeneutics who translated Steenbrink’s ‘Jesus in the Qur’an’ (on Sūrat Āli ʿImrān and Sūrat Maryam) into Bahasa Indonesia, categorizes Steenbrink’s methodology as the interpretative approach of a non-Muslim who has studied the Qur’an and wants to explain to non-Muslim readers the truth about it. The Second Vatican Council’s 1965, ‘Nostra Aetate’, which acknowledges the truth in other religions, including Islam, might shape his theological orientation, but his experience as an anthropologist who used a phenomenological method in his research definitely influenced his approach to translating Qur’an.

Yulia Riswan