Some translations are known for their controversial choices. Others come across as ostensibly uncontroversial, which is precisely their point and their selling proposition: Addressing those many Muslim and non-Muslim readers that have no predetermined ideological expectation of a Qur’an translation, they strive to represent a ‘middle way’ and to avoid flagging any kind of sectarian affiliation.

A good example of this is the recent French translation by the convert Abdallah Penot (formerly called Dominique Penot, a name under which his books are often sold in Turkey but not in France). Born in France in 1954, he became enthralled by the writings of the esotericist René Guénon (1886–1951) who ended up living in Cairo and becoming a Sufi sheikh. Penot was originally more interested in India and Hinduism than in the Arab world and Islam, but on the way to India, he stopped off in Damascus, where he ended up staying for seven years. After converting to Islam, he studied with a Sufi sheikh, learned Arabic, delved into various branches of religious learning and came back to France in the early 1980s as a master of the Shadhiliyya Sufi order. Since then, he has been active in realizing his mission of bringing not only Sufism, but also traditional Islamic learning to French Muslims. This involves using pedagogical models that emphasize the personal instruction of a student by a learned master ‘through uninterrupted chains of transmission,’ offered at his ‘institute asharite’, as well as publishing works of traditional Islamic scholarship in French in his own publishing house, ‘Alif éditions.’ He has translated many of these works himself, including books by renowned Sufis such as Ibn ʿArabī and ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazāʾirī, but also books that are generally popular among Sunnis such as al-Nawawī’s hadith collection Riyāḍ al-Ṣāliḥīn. Among the books he has authored himself, his L’Entourage feminin du Prophète (‘The Prophet’s female entourage’) is particularly popular.

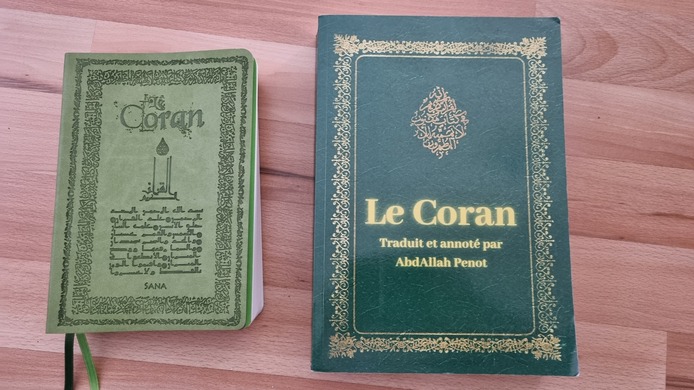

The first, monolingual French edition of his Qur’an translation was published in 2005 by Alif éditions as a pocketbook, with a bilingual version 2006 and various subsequent reprints. In 2019, a revised bilingual Arabic-French edition came out, printed and distributed by Librarie Sana, a company based in Paris and Lyon that produces and trades in Islamic books, educational games and prayer rugs. The new bilingual edition is beautifully designed with a suede cover in different colors as well as matching ribbon bookmark, calligraphy and highlighted items in the text (such as the names of God). This trend towards producing aesthetically pleasing books that offer readers a choice of designs and colors has been adopted by a number of Islamic publishers in France and seems to be quite popular with readers, some of whom discuss in their reviews on shopping websites whether the shade of green of the book they received matches the expectations raised by the pictures on the website, rather than rating the content.

Aesthetics aside, the typesetting of the new edition, presumably carried out by the publisher and not by Penot himself, has been implemented somewhat carelessly. The headers carry the sura numbers, as well as the number of the division, or juzʾ, of the Qur’an, which confusingly is called ‘chapter’ (‘chapitre’) – a mix-up that resulted in Sūrat Maryam being numbered as Sura 16, rather than 19. The publisher has also tried to make the book generally more appealing to Muslim readers, not only by adding Arabic sura titles to Penot’s French ones but also by Arabizing the basmala at the beginning of each sura. It is rendered as ‘Au Nom d’Allah, Arrahmân, Arrahîm’ (‘In the Name of Allah, Arrahmân, Arrahîm’), rather than Penot’s less ostensibly Islamic, but more easily comprehensible ‘Au Nom de Dieu, le Tout-Miséricordieux, le Très-Miséricordieux’ (‘In the name of God, the All-Merciful, the Very Merciful’).

Ease of comprehension was at the top of Penot’s list of priorities when translating. In the introduction, he discusses the reasons he produced another translation of the Qur’an when so many French translations were already available, especially since it is clear, according to him, that any attempt at finding the one key to solving the mysteries of the Qur’an – be it numerology or cosmology – is futile. However, he argues, it is precisely because of the infinite number of meanings contained in the Qur’an and the wide variety of approaches a translator may legitimately take, each of which has its merits and its drawbacks, that every new translation will add a new perspective without ever being able to make all others superfluous. Thus, Penot explicitly does not claim to have produced the best or most authoritative translation, but merely to have made a contribution that has its own merits and drawbacks (although, despite this show of modesty, he does not state which drawbacks his translation might have). His aim, he says, is to address general readers who are unfamiliar with even the most basic tenets of Islam and make the Qur’an accessible to them without betraying its meaning. For this reason, he explains, he has kept the amount of commentary to a minimum and rarely draws on Qur’an commentaries that are more extensive than the Tafsīr al-Jalālayn and the tafsīr by Ibn Juzayy (he mentions that on those rare occasions he does, the commentaries by al-Ālūsī and al-Qurṭubī are among his sources). Stylistically, he has aimed for a middle path between the literal and the literary, and mentions the translations by Hamza Boubekeur and Sadoq Mazigh as his models for each of these approaches. In terms of exegesis, he avoids radical, polarizing interpretations, especially those that are modernizing or excessively historicizing. Instead, he has aimed for non-controversial readings, while emphasizing his belief that all the verses have deeper spiritual and esoteric meanings in addition to their apparent ones.

However, Penot’s acknowledgment of his Sufi convictions is rarely reflected in the actual translation, presumably because that would in itself be controversial. There is, for example, no esoteric translation of the disjointed letters at the beginning of suras; rather, they are not explained at all. Only very occasionally does Penot make reference to Sufi beliefs, primarily in his footnote on the story in Sūrat al-Kahf (Q 18) of Moses’s travels with a companion who is unnamed in the Qur’an but identified by most exegetes, and also by Penot, as al-Khiḍr. Here, Penot points out that Moses, even though he is a prophet, is depicted as being inferior to his travel companion, who is not a prophet but is still tasked with teaching Moses a type of knowledge that the latter is lacking. This knowledge has been identified by many as Sufism, and the story characterized as illustrating the relationship between master and disciple, Penot argues. Generally, he strongly defends the doctrine of the infallibility and sinlessness (ʿiṣma) of prophets.

Often, when writing on such doctrinal issues, it becomes clear that Penot’s projected readership predominantly consists of non-Muslims with a Christian background. For example, in his note on Q 2:2, he translates the term muttaqūn, which many translators render as ‘pious’ or ‘God-fearing,’ as ‘those who wish to protect themselves’ (‘ceux qui veulent se prémunir’). This is one of the instances in which he adds not only a footnote but a section of commentary to his translation. (These are sometimes inserted below a segment from the Qur’an, and sometimes placed in an appendix.) In this case, he adds a comment below Q 2:1–5, in which he explains how he derived his translation of muttaqūn from the root of the verb ittaqā and goes on to say:

‘The idea that we can protect ourselves against God is confusing for non-Muslims and especially for Christians, for whom God is Love. Without denying the notion of divine love, Islam insists on the fact that everything comes from God (kullu min ‘indi llâh), guidance as well as aberration, and that we should ask Him to protect us from His devices (makr) with the same insistence that we should ask Him to make us one of His chosen ones.’

The first edition had contained an even longer explanation and also included the option of translating muttaqūn as ‘the pious ones,’ but in the latest edition Penot has discarded this in favor of accessibility and clarity. The translation still contains references to alternative meanings and interpretations, but in most cases, even when the meaning of an expression in the Qur’an is rather controversial, Penot chooses to provide one meaning only without any indication that there might be other options. For example, the term al-sāʾiḥūn in Q 9:112 is understood by the majority of premodern exegetes to mean ‘fasting,’ while others, especially modern interpreters, understand it more literally as ‘wandering the Earth’ or ‘travelling,’ but it is translated by Penot without further comment as ‘pilgrims,’ which is an opinion that does exist in the tafsīr tradition but is certainly a minority opinion.

When it comes to verses that are especially controversial from a contemporary perspective, such as Q 4:34 which has often been denounced as ‘the wife-beating verse,’ Penot opts for translations that are neither disruptive to the exegetical tradition nor starkly offensive, especially to non-Muslim readers. Thus, instead of rendering wa’ḍribūhunna as ‘and beat them,’ he writes ‘and discipline them’ (‘et corrigez-les’).

When translating verses that use anthropomorphic attributes to describe God, which are contested between Salafis and traditional Ash’ari and Maturidi scholars, Penot usually opts for a literal translation: he talks of God’s throne, rather than God’s all-encompassing power or wisdom, for example, and he has no issue with the expression ‘God’s face’ either, leaving it to readers to decide whether they favor a literal or metaphorical understanding of these expressions.

Penot’s translation is a good example of a Qur’an translation that tries to satisfy a variety of target groups, including both non-Muslims and mainstream Sunni Muslims, and has therefore shown a potential for commodification. That said, in the highly competitive French Qur’an translation market, it is still only one translation among many, neither obscure nor wildly popular.

Johanna Pink