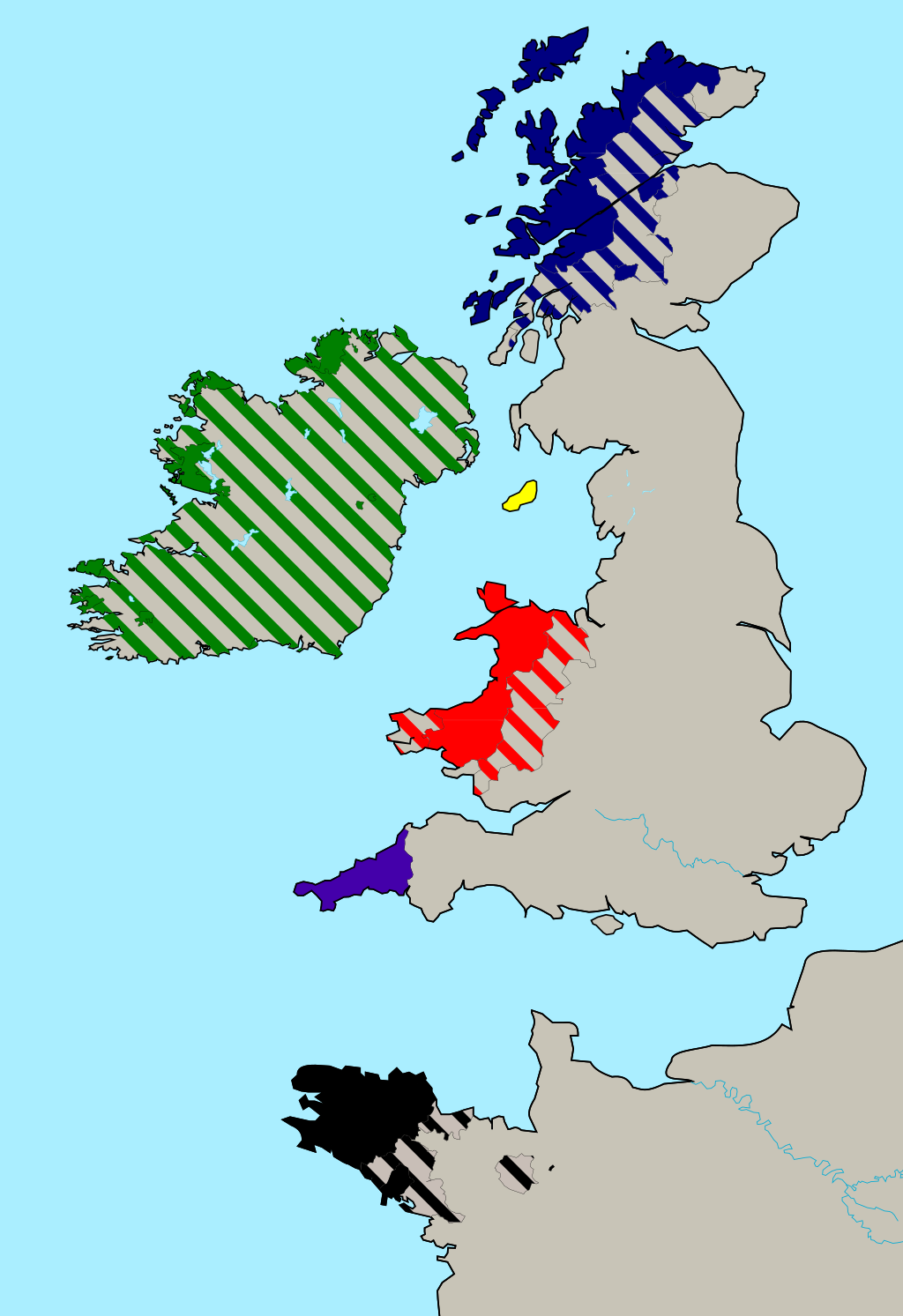

The Qur’an has been translated into dozens of languages, but there are many more languages in which no full translation is available. Examining partial, ongoing, unsuccessful or nonexistent attempts at translating the Qur’an into any given language can shed light on its present-day condition, its status in a specific region or country and the demographics of a particular community of speakers. If we look to the Celtic languages, which have endured a history of marginalization and sometimes downright oppression, we find that no full Qur’an translation into any of them exists. However, in all four living Celtic languages – Breton, Welsh, Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic – some translation projects have been reported (whereas there are none in Cornish and Manx, which were both extinct before efforts to revive them in recent decades).

Muhammad Hamidullah drafted an extensive list of Qur’an translations into a wide range of European languages in 1959, which was updated in the 1970s. It contains two items in Breton, two in Irish and one in Scottish, all dated to the 1940s and 1950s, which looks impressive at first glance. However, they are all described as manuscripts covering a small number of selected verses. None of them seems to ever have been published, and the authors were all non-Muslims with whom Hamidullah apparently was in private contact, including the ‘very likeable official translator of the parliament in Dublin.’ In short, all of these items seem to be related to personal notes, rather than actual translation projects.

The only printed (partial) Qur’an translations into Celtic languages go back to the Ahmadiyya movement, which published ‘Selected Verses of the Holy Qur’an’ in Welsh in 1988 and Irish in 1989. This was part of a concerted effort to translate a thematically arranged selection of segments from the Qur’an into 101 languages in celebration of the centenary of the foundation of the Ahmadiyya movement. The languages chosen included many minority languages but also more widely spoken ones, such as English, Italian, Malay and Persian. The booklets always covered the same segments of the Qur’anic text, divided into 20 sections on topics such as God, Angels, Worship, Women, and Supplications from the Qur’an, and typically contained between 60 and 70 pages. They were translated from the Ahmadiyya’s English version of the ‘Selected Verses,’ which would have made it much easier to find translators into Welsh and Irish than it would have been for a translation from the original Arabic. That this is a serious problem was admitted by the spokesman of the Irish Ahmadiyya community in Galway in 2017 when the community was hatching plans for producing a full translation into Irish Gaelic but failed to find anyone with a sufficient level of skill in both languages. He expressed the hope that, given the rising number of Muslims in Ireland, the increasing efforts to promote and teach Gaelic in Ireland, and the institutionalization of Islamic education, a qualified translator might emerge in the long term.

The Ahmadiyya movement is rejected by the majority of Muslims today, however, and most of them do not consider their Qur’an translations acceptable. For this reason, there are periodic reports about new translation projects into the Celtic languages which never even mention the Ahmadiyya publications. However, none of these projects have come to fruition yet, and this is typically due to the same problems the Ahmadiyya faced. Of the four languages, Irish Gaelic has the strongest and most secure status, given that it is the official language of the Republic of Ireland, but the number of speakers who use it in their daily lives outside the education system is probably only around 100,000. In 2003, Foras na Gaeilge, a public institution in charge of the promotion of the Irish language in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, joined forces with the Islamic Cultural Centre of Ireland and set up a committee for translating the Qur’an to Irish, which they thought might take them one year. However, they aborted the project when no suitable translator could be found.

An identical problem occurred when, in 2008, the Muslim Academic Trust in the United Kingdom set up a £5o,000 project to produce a Scottish Gaelic translation of the Qur’an, funded by a Muslim from Dubai. They likewise failed to find anyone who knew both Gaelic and Arabic well enough to undertake the work. There were thoughts of establishing a committee and using English translations, rather than translating from the original Arabic, but there is no indication that this has actually happened.

Turning to France, in 2015 the Sunna Mosque in Brest (now called ‘Islamic Cultural Centre’) announced its intention of producing a Breton Qur’an translation as part of its effort to integrate into Breton society. The leadership of the mosque community signed a charter pledging to strengthen the Breton language and promised to offer trilingual Arabic–French–Breton sermons, use Breton on their website and as a language of instruction, and work on a Qur’an translation into Breton. This was apparently strongly pushed by Jean-Marie Seiget, a Breton convert to Islam and retired professor. Once again, and this probably does not come as a surprise by this point, the project does not seem to have to come to fruition, nor has the Breton website materialized.

Welsh is a latecomer on the scene: in October 2022, BBC Radio Cymru reported that Laura Jones, a practicing Muslim who was at that time a PhD student in Cardiff, was planning to translate the Qur’an into Welsh. She had studied Welsh at school but only became an active Welsh speaker as an adult and described herself as being partly motivated by the desire to express her Islamic faith in Welsh. She had started producing Welsh translations of Islamic texts while working for the Muslim Council of Wales. While in the past there might not have been many Welsh-speaking Muslims, she said, this was starting to change, given the increasing number of Muslims who learned Welsh in school, for example. In this case, it is too early yet to say whether her project will be another nonstarter or will result in the first full Qur’an translation into a Celtic language.

The main reason it has proved so difficult to produce a Celtic translation has to do with the history of this group of languages. France has historically actively tried to erase minority languages, including Breton, especially through educational policies. When it comes to the British Isles, the official policy agenda may have been less oppressive, but under the rule of the English crown the Gaelic languages could not compete with the prestige, power and usefulness of the English language and their use was therefore gradually eroded. The remaining speakers were often concentrated in rural, less socially and geographically mobile communities which were solidly Christian. The proportion of Muslim immigrants in these regions was low and, besides, the benefits of acquiring knowledge of a Gaelic language, as opposed to the dominant English or French, were minimal.

Why are there even efforts at producing Qur’an translations into Celtic languages, then? For the Ahmadiyya community in particular these translations demonstrate the global reach of their daʿwah efforts, to which multilingualism has been central from the outset. The mere fact of the number of languages that they cover is a boost to the status of the movement, especially given that the Ahmadiyya is the only community that has ever managed to produce even so much as an excerpt from the Qur’an in a Celtic language. For other Muslim individuals and communities, the goal has not so much been global outreach but rather the increase of their community’s local or regional status and networks. This is especially visible in Ireland, where since the 2o00s significant political efforts have been made to strengthen the Irish language, and in Brittany, where the Sunna Mosque of Brest tried to connect with wider attempts at making the Breton language more visible. Moreover, it is noteworthy that in most of the projects documented here, converts seem to have played a central role. These Muslims had grown up in Celtic-speaking regions and obviously felt a desire to connect their Islamic faith to their local roots.

All this is taking place in a context in which the prestige of Celtic languages has been rising steadily for several decades. They are increasingly perceived as endangered but valuable cultural assets worthy of protection, rather than as markers of a rural lower-class background. However, in sociolinguistic terms, all Celtic languages suffer from a gap between their prestige and their utility. While their prestige has noticeably increased in recent decades, their utility is still extremely limited, given the universal spread of either English or French in the regions in which these languages are still spoken. Thus, those who express appreciation for Celtic languages on a declarative level are still not likely to use them in their everyday lives or have sufficient mastery of them to produce a Qur’an translation, and this explains the many stalled and thwarted efforts at translating the sacred scripture of Islam into Gaelic, Breton or Welsh. Still, many people living in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Brittany today consider the local Celtic language to be an important part of their identity that distinguishes them from England and France, respectively, and the call to translate the Qur’an into Celtic languages is part of this process of identity formation.

Johanna Pink