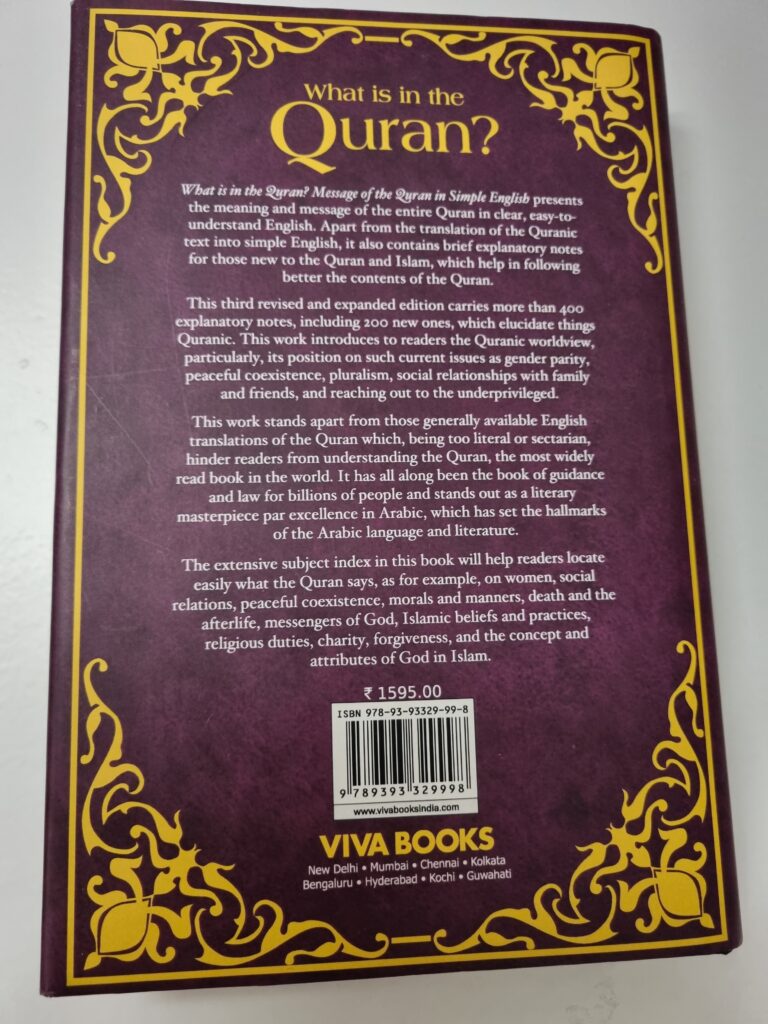

Abdur Raheem Kidwai (b. 1956), currently director of the K.A. Nazmi Qur’anic Centre at Aligarh Muslim University in India is not only a well-known reviewer of other people’s Qur’an translations into English, but also a translator himself. His own translation, What is in the Quran? Message of the Quran in Simple English (first published in 2013) has already seen three editions, with the most recent (revised and expanded) edition being published in 2023 by Viva Books in New Delhi. Other works published by Kidwai include three informative bibliographies of Qur’an translations (The Bibliography of English Translations of the Meanings of the Glorious Qur’an into English, 1949–2002 in 2007, Translating the Untranslatable in 2011, and God’s Word, Man’s Interpretations in 2011).

The Bibliography of English Translations, which wasprinted by the Saudi King Fahd Glorious Qur’an Printing Complex, reviews over 70 translations, and Kidwai’s statements on the merits or otherwise of such and such work sometimes appear to provide an ‘evaluation’ that answers, in particular, the much-debated questions over whether a given translation is ‘good enough’ for believing Muslims to read and cite or not. Usually in his reviews Kidwai (who holds PhDs in English literature from Aligarh and Leicester universities) favors mainstream Sunni or Sunni-Salafi translations, and is very critical of any Shii or Ahmadi interpretations. However, in an apparent departure from this, Kidwai lists interpretations with quite different approaches among the translations he found ‘useful’ in the bibliography appended to his own translation of the Qur’an. Here one can find, for example, the 1987 edition of Abdul Majid Daryabadi’s The Glorious Qur’ān: Text, Translation & Commentary; Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s The Meaning of the Holy Qur’ān (the Amana Corporation edition from 1989); and Taqi al-Din al-Hilali and Muhammad Muhsin Khan’s The Noble Qur’an (Darussalam edition from 1994), the last of which is a byword for Salafi exegesis. It also notably includes a recent translation entitled The Qur’an with Reference to the Bible, a joint project by two Muslim and Christian theologians, Safi Kaskas and David Hungerford, published in 2016.

When describing his own interpretation, Kidwai says that ‘the present work is not, strictly speaking, an English translation of the Qur’an. It attempts to present in simple, fluent English the paraphrase of the meaning and message of the Qur’an.’ This orientation towards a ‘reader-friendly’ approach is fairly innovative when it comes to Qur’an translations, and could be compared to an existing approach taken in some translations of the Bible (for example, The Bible in Basic English by Samuel Hooke, 1941). It is not clear who Kidwai’s main target readership is, but his translation seems to be aimed at people with a limited knowledge of the Islamic tradition and/or those for whom English is a second language.

This does not mean, however, that Kidwai provides only the core text of the Qur’an in his rendition: while his compatriot Maulana Wahiddudin Khan provides no footnotes or commentary in his translation of the Qur’an, which is also designed for a popular readership (The Qur’an, 2009), Kidwai includes plenty of both. In just the first fifteen pages (Q 1:1 to Q 2:151) there are about 50 footnotes introducing basic Islamic tenets and concepts (out of a total of 410 for the whole book). Despite this, Kidwai takes a very simple approach and almost never refers to any Arabic terms or justifies his word choices. For example, in Q 1:2, he translates the epithet rabb al-‘ālamīn as ‘Lord of the universe’ without going into any discussion of his reading of al-‘ālamīn as ‘the worlds’ or even ‘inhabitants of the worlds,’ as do some other interpretations. Likewise, the very frequently occuring Qur’anic pronoun nahnu (‘We’), which often is used in the sense of God referring to Himself, is never translated literally: for Q 15:9, innā nahnu nazzalnā l-dhikru wa-innā lahu la-khāfiẓūn, Kidwai writes: ‘God has sent down this message (The Qur’an) and He is its protector.’ One might expect that as this is a general feature of his translation, and seems to have been intentionally made to contrast with other English interpretations, Kidwai would provide the reader with some kind of discussion of the rationale behind this choice, but the only hint that can be found in Kidwa’is introduction is a statement about ‘taking some liberty … choosing such pronouns which fitted within the context’. This is one of a number of literary features that completely detaches Kidwa’is translation from the stylistics of the Arabic Qur’an, but this is only to be expected from a rather pragmatic, ‘simple’ English translation.

Without going into any theological debates, despite Kidwai’s claim to ‘simplicity’ and neutrality, the translation is not free from polemics when it comes to issues such as gender or interreligious relations. It would be hard to enumerate how often Kidwai uses expressions like ‘gender justice,’ ‘gender equality,’ and ‘gender parity’: such terminology is used frequently in his rendition of the first 40 verses of Q 4 (Sūrat al-Nisāʾ, ‘The Women’). Kidwai even finds room to bring ideas of Islamic respect for gender equality into his translation of Q 52:24, which mentions (male) ‘youths,’ using the word ghilmān in its masculine form. Translating this verse as ‘Youths’, as beautiful as untouched pearls, will serve them’, he comments that ‘The Qur’an maintains remarkable gender parity in mentioning the beautiful, ever-young youths along with the alluring houries in Paradise’ (fn. 359). Just one page earlier, in his translation of a verse that mentions those Qur’anic houries (ḥūrin ʿayn, Q 52:20), Kidwai uses the word ‘damsels’, probably not the best choice for a ‘simple English translation,’ since, for example, the Cambridge Dictionary describes this noun (which it says means ‘a young, unmarried woman’) as being of ‘old use,’ which implies that it is not necessarily easy to understand. Kidwai frequently mentions the Bible, referring to characters such as Moses and David, and talks about the common grounds of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (in a footnote to Q 3:4 he favourably mentions Gabriel S. Reynolds’ book The Qur’an and the Bible, 2018). However, his views on Christianity sometimes appear to be strange. For example, in his footnote to Q 52:20, he says: ‘In Islam, unlike Christianity, physical joys, including sex within marriage, are not forbidden.’ One may guess that by this he is referring to some Catholic or Protestant fundamentalist views about sex as something ordained with the purpose of procreation as its natural end (‘transmission of life’), but this obviously does not accord with many other contemporary trends in Christian theology. In addition to bringing in such discourse on gender and interreligious issues, Kidwai usually tries to emphasize unique features of the Islamic message: for him Q 32:27 (‘… He thus lets the same land produce with the water crops which they and their cattle eat …) was sent down to ‘sensitize’ people to ‘Animal Rights as far back as in 7th century.’

Over ten years on from the publication of the first edition of this translation, it is hard to call it really popular. Printed by local Indian publishers, it is difficult to see how it competes with other existing interpretations in English, even among Indian Muslims, despite it being a forerunner in the genre of ‘simple’ translations and the fact that it mostly represents mainstream exegetical ideas. It seems that Kidwai’s reviews of other Qur’an translations, although sometimes controversial (as many critics note), have had more impact than his own translation.

Mykhaylo Yakubovych