This week our attention focuses on the translation made by one of the most charismatic Muslim preachers in contemporary Russia, Shamil Alyautdinov (b. 1974). An Imam in Moscow, he holds various titles in the Muslim Spiritual Administration of the European Part of Russia (DAMER). Alyautdinov is author of more than thirty books and, quite uniquely for an imam, is also a popular Muslim coach. In his teachings and trainings, he emphasizes the importance of success in both worlds, which manifests in the titles of his books and seminars such as “Trillionaire” and “Be the Smartest and the Richest”. His Qur’an translation, first published in 2012, targets a wide range of potential readers. There are three formats in which the translation can be purchased: an impressive four-volume edition with Russian and Arabic texts intended for leisurely reading at home; a smaller version also with Arabic text; and a one-volume book only in the Russian language. Alyautdinov’s translation is also available for free online on his website, Umma.ru.

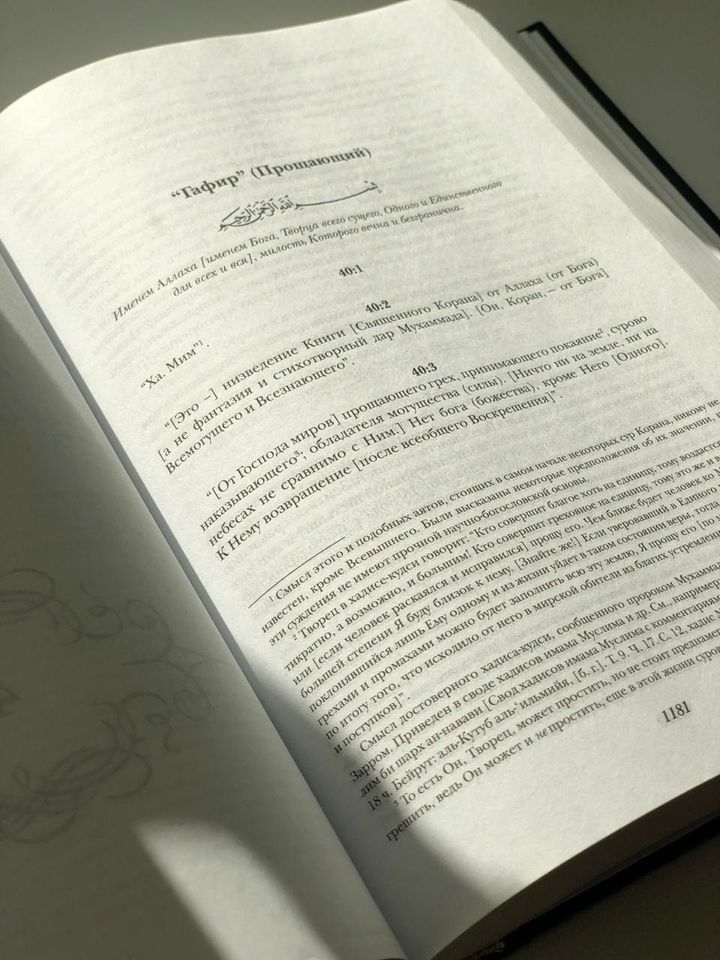

As an Azhar-trained Muslim theologian, he likes to emphasise that his work is distinguished from the rest as it is “theological” and thus a reliable translation by a qualified Muslim scholar. (Bogoslovsky perevod). However, contrary to what one might assume, this does not mean that the work is references works of classical exegetes exclusively. Alyautdinov cites classical and modern, Arabic and Turkish scholars, but what is especially notable in his work is the extensive thematic digressions after certain āyāt. Some parallels could be drawn with the post-classical Islamic genre of Qur’an commentaries which sometimes list ‘points of benefit’ (fawāʾid), often clarifying some spiritual dimension of the verses. In Alyautdinov’s case, these thematic digressions are very variegated and they include legal, ethical, and theological themes. They sometimes even appear in the form of a fatwā, where Alyautdinov answers a potential question related to the verse.

cover_1.jpegSignificantly, Alyautdinov does not try to hide his voice as a translator and commentator, and these thematic degressions serve as a place for Alyautdinov’s edifications and thoughts. His “translation” is in fact an extensive tafsīr through which he tries to make the Qur’an’s meanings relevant and engaging to a broad post-Soviet readership. In this context, it is not surprising to find references to the Bible; Soviet poets like Samuil Marshak (d. 1964); popular Hollywood films like The Kingdom of Heaven (2005) that penetrated Russian TV after the fall of the USSR; and even singers such as Vladimir Vysotsky (d. 1980) who is cherished by many people in Russia across different ethnicities.

His theological and legal digressions can be seen as an attempt to introduce the central religious practices and beliefs around which a pious Muslim life is structured. For example, if a verse mentions wuḍūʾ or ghusl, Alyautdinov provides an explanation of how ablution should be performed. The theological digressions include some pertinent topics like the symbolic meanings of the Ka’ba as a locus of unity for Muslims (rather than “the house of God”), or the explanation of Jesus’s ascension and the Muslim perspective on the crucifixion. Among the ethical digressions, there are multiple themes about appropriate Muslim morals and good conduct. Through all these themes inserted within the Qur’an translation, Alyautdinov tries to internalise his vision of a good Muslim life in its practical sense.

While Alyautdinov’s translation is written in accessible language overall, he does use many Russian words that can be called obsolete, technical, or academic. This can be seen as an educational strategy, as Alyautdinov adds explanatory footnotes for these words. For example, he clarifies such words as smradny, transcedentny, ezotericheskiy, and prezumpciya. A particular feature in terms of language is that Alyautdinov does not see the need to make a translator’s choice for the word Allāh; he uses the Arabic name and the Russian words Bog and Gospod’ interchangeably – or, more often, all together in brackets. He applies the same strategy for Iblīs, which he writes together with Dyavol, Satana, Shaytan as equivalents. In relation to the Prophets and other characters mentioned in the Bible, this combination of names allows both Muslims and Christians to recognize the Qur’anic characters easily; perhaps it is intended as a rhetoric tool through which readers can relate their Christian knowledge to Qur’anic stories.

In the Bibliography, Alyautdinov includes only seven main references. However, it becomes clear throughout the pages that the scope of the sources is much wider and it includes almost all kinds of Muslim intellectual strands from the Sufi al-Qushayri (d. 1074) to the Muslim thinker Sayyid Qutb (d. 1966) – although strictly without his political discourse. Alyautdinov’s translation is a demonstrative example of what Tymoczko (2007) called ‘transculturation’ in translations which implies cultural adaptations and borrowing. Moreover, ‘transculturation’ implies performativity in its various forms including the value systems. This can also be found in Alyautdinov’s translation: e.g., in one thematic digression, Alyautdinov emphasises that the exemplary Muslim life is when “one at twenty-five is already a PhD, at thirty a professor, at forty an academic who is the best in his area.” The modern ethos of success and personal development – but with Islamic underpinnings – is a key message in Alyautdinov’s discourse (Bustanov 2012; Benussi 2020) which saturates his books and seminars and can be seen clearly in this very original Qur’an translation.

Elvira Kulieva