Today’s post discusses a Lebanese publisher’s attempt to bridge the divide between non-Muslim and Muslim French Qur’an translations by editing and repackaging the Qur’an translation by Denise Masson (1902–1994) for a Muslim audience.

That such a divide exists is true of most European book markets. On one side of the divide, we find mainstream publishers that distribute the works of non-Muslim translators – often Orientalists – in high-street bookstores to non-Muslim readers who are either curious about Islam or critical of it. The translations in this segment are commonly simply entitled ‘The Qur’an’. On the other side of the divide, we find Islamic publishers that are often semi-professional and frequently based in Turkey or the Arab world. They target their Qur’an translations at a readership of practicing Muslims and distribute them in Islamic bookstores and mosques. The translators of these works are invariably Muslim. The titles of their works involve honorifics (‘The Noble/Sacred/Inimitable Qur’an’) and emphasize the difference between the translation and the actual Qur’an (e.g. ‘Translation of the meaning of the verses of the Noble Qur’an’). They are often bilingual, containing the Arabic text alongside the translation.

In the non-academic Muslim field, in mosques and Islamic bookstores, the works of non-Muslim translators are typically mostly ignored or, alternatively, viewed with distrust. A few translations by non-Muslims are granted a certain degree of recognition as honest and benign endeavours, but this does not mean that religious scholars, imams, and other Muslim stakeholders recommend their use or that they are marketed to Muslim audiences.

The French Qur’an translation by Denise Masson probably belongs to the last category, i.e. that of works which, when Muslim scholars have taken notice of it, were considered acceptable and non-hostile. It was first published in 1967 under the name ‘D. Masson’, which was probably an attempt to disguise the author’s gender, in the famous series Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. This might be the most distinguished and prestigious venue that French literary publishers have to offer. The series, which has its origins in the 1930s, is renowned for its critical editions and original translations of the classics of world literature. It publishes them in an identical compact format that is both unassuming and luxurious, with leather binding, gold stamps, and bible paper.

Masson was a Christian intellectual from a rich French family who spent much of her life in Morocco and acquired an in-depth knowledge of classical Arabic and the modern Moroccan dialect. Her translation of the Qur’an was based on years of study of the relationship between the Hebrew and Christian Bibles and the Qur’an. It came with a lengthy introduction, extensive notes, and an index. The introduction generally follows Muslim views of early Islamic history and is highly sympathetic towards Muḥammad and the Qur’anic text. Masson’s translation was widely credited with being elegant, concise, respectful of the Qur’anic text, and with capturing some of its rhetorical and spiritual impact. Today, it is also available in a paperback edition and is widely sold in high-street bookstores in France. It is, however, not commonly found in mosques or Islamic bookstores.

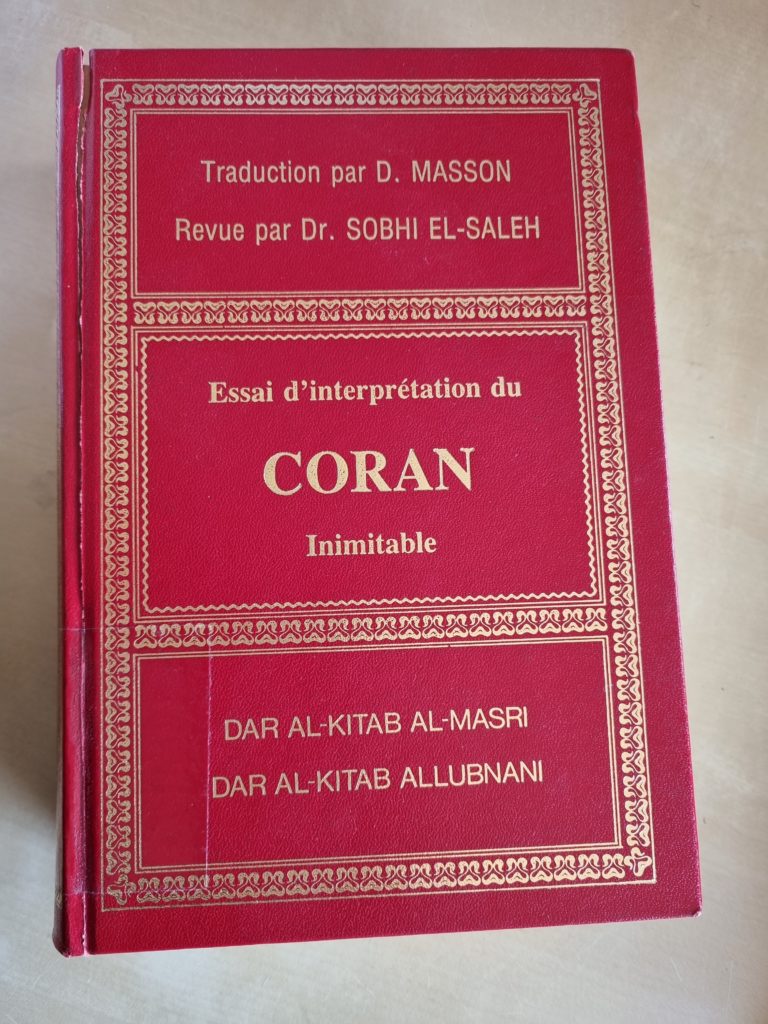

In 1980, the Beirut-based publisher Dār al-Kitāb al-Lubnānī published Masson’s translation with the clear intention of marketing it to a Muslim audience, possibly primarily within Lebanon itself. They renamed it to Essai d’interprétation du Coran Inimitable (‘An Attempt to Translate the Inimitable Qur’an’) and added the Arabic text of the Qur’an as well as an Arabic index of suras. A different edition is entitled Traduction des Sens du Saint Coran (‘Translation of the Meanings of the Holy Qur’an’). The Arabic cover bears the title Tarjamat maʿānī al-Qurʾān al-karīm bi’l-lugha al-faransiyya (‘Translation of the meanings of the Noble Qur’an in French’).

The book contains certificates of acceptability from the Lebanese Dār al-Iftāʾ (Fatwa authority) and from al-Azhar’s Islamic Research Academy. (Incidentally, the certificate from al-Azhar is dated 1985 while the book itself is dated to 1980, which raises the question of whether the al-Azhar certificate was added to a second edition.)

On the French cover, the translation is attributed to ‘D. Masson’. A prominent addition states, ‘Revised by Dr Sobhi El-Saleh.’ Sobhi El-Saleh (Ṣubḥī al-Ṣāliḥ) was a prominent Lebanese Sunni scholar and university professor, and in the Arabic segments of this book, it is exclusively his contribution that is visible whereas Masson’s name is nowhere to be found. The Arabic cover pages mention El-Saleh, but not Masson, and both the Arabic and French cover pages list El-Saleh’s posts and functions but not Masson’s. Thus, Masson’s name is only marginally present, and only in the French parts of the book, while it is the male, Lebanese, Muslim scholar’s role that is highlighted.

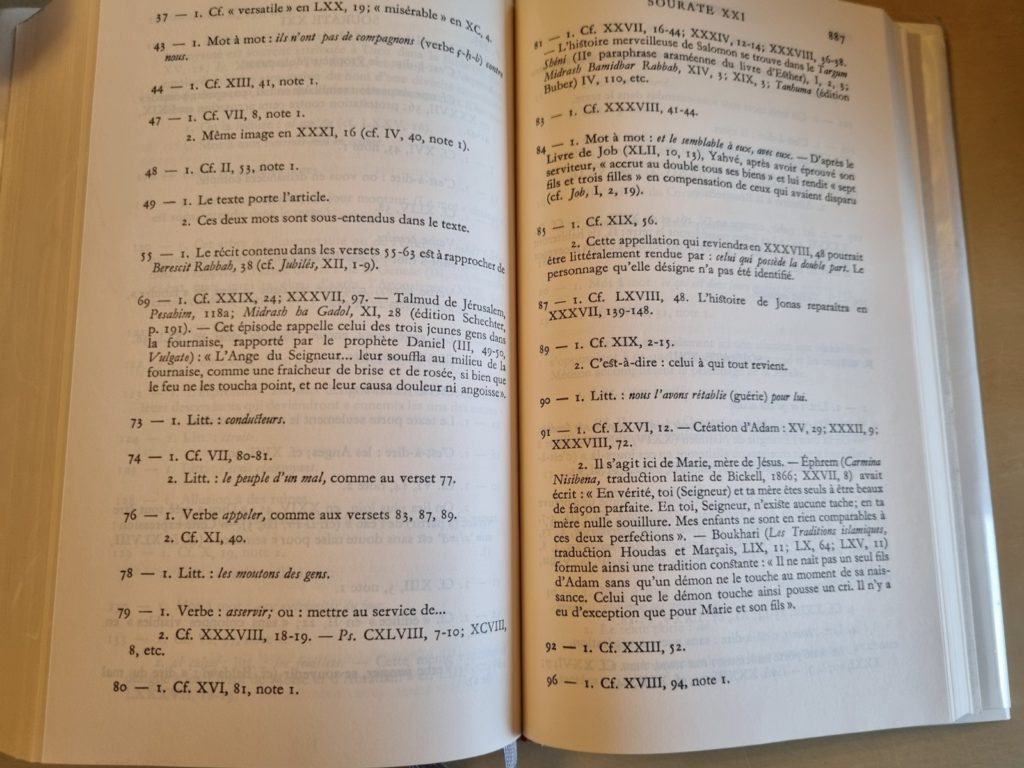

Masson’s lengthy introduction is missing from the Lebanese edition, with the exception of a few pages on the semantic choices she made in her translation, and her notes have been shortened significantly: most notably her copious references to historical circumstances and biblical parallels have been excised. The foreword by the French poet Jean Grosjean, however, was not deleted. Grosjean’s name – mentioned prominently on the Pléiade cover but not on that of the Lebanese edition – had provided authority and prestige to this book for the intended readership of cultured, well-to-do French people. Since Dār al-Kitāb al-Lubnānī targeted a different audience, Grosjean’s name would not have been sufficient to lend credibility to the book, which is why they focussed on emphasising El-Saleh’s contribution, despite the fact that his edits of Masson’s text are minimal, at least with regard to the actual text of the translation.

These edits are fairly easy to identify because the Lebanese publisher reused the typescript of the Pléiade edition, which they reassembled in a cut-and-paste fashion to match the Arabic muṣḥaf. This results in a somewhat uneven layout; moreover, in the first sura, one line has been accidentally deleted (‘le Miséricordieux’ for al-Raḥīm in v. 3, a translation that is present in all other occurrences of the Basmala and has therefore obviously not been consciously deleted). El-Saleh’s edits were typeset in a different font, either in boldface or a sans serif font, and then pasted into the text. Going through the whole translation, I have found only five such edits. There was thus no extensive interference with the text, no replacement of ‘Dieu’ with ‘Allah’, or similar Muslim-signalling, and the five changes I found seem relatively inconsequential.

Two of the five changes concern the Arabic term al-nabī al-ummī (Q 7:157, Q 7:158) which refers to Muḥammad. Masson originally translated this as ‘le prophète des infidèles’ (‘the prophet of the unbelievers’), and El-Saleh changed it to ‘le prophète qui ne sait ni lire ni écrire’ (‘the prophet who can neither read nor write’), which is generally how the Muslim exegetical tradition understands it. In her introduction, Masson, too, subscribed to the view that Muḥammad was illiterate, but in the context of these verses, she, like many Orientalists, understood ummī to mean a prophet who was sent to the Gentiles, as opposed to the prophets of the Jews and Christians. El-Saleh does mention this possibility in the note to Q 7:157. Interestingly, the same type of revision was made by the King Fahd Complex in their edition of Muhammad Hamidullah’s 1959 French Qur’an translation, in which ‘the gentile prophet’ was replaced with ‘the unlettered prophet.’

Two further changes relate to the translation of the Arabic verb ʿahada. In both cases, it occurs in a context where God is speaking about his interaction with biblical prophets: Abraham and Ishmael (Q 2:125) and Adam (Q 20:115) respectively. Masson understood the verb to mean ‘We have concluded/established a pact’ whereas El-Saleh understood it as God having entrusted the above-mentioned prophets with a mission (‘Nous avons confié une mission’).

The fifth change concerns Q 3:10. In contrast to the preceding examples, which do have an impact on meaning, it does not make any sense at all. Masson has ‘Les biens et les enfants des incrédules ne leur serviront à rien auprès de Dieu’ (‘The goods and children of the disbelievers will be of no use to them before God’), which El-Saleh replaces with ‘Quant aux incroyants ni leurs bien [sic] ni leurs enfants ne leur seront d’aucune utilité auprès de Dieu’ (‘As far as the unbelievers are concerned, neither their good [sic] nor their children will be of any utility to them with God’). This does not seem to make any difference to the meaning of the verse but it converts Masson’s fluent French sentence into one that is based on Arabic syntax and is not entirely grammatically correct. Moreover, in his translation, El-Saleh uses different terminology, but without following up on this choice in any other part of the translation. Masson makes a point of rendering kāfirūn as ‘incrédules’ throughout her translation, a decision that she explains in her introduction. The edition by Dār al-Kitāb al-Lubnānī completely follows that choice, except in this singular instance where Masson’s translation is changed and the term ‘incroyants’ is used instead of ‘incrédules’. One wonders whether El-Saleh, or a different editor, looked at a random sample of the text and replaced it with a more literal translation, either for symbolic reasons or to justify his attribution as the person in charge of revising Masson’s translation.

It is hard to say whether the publishers were successful with their attempt to sell this translation to Muslim audiences. There seem to have been several editions published in the 1980s, before Dr El-Saleh’s untimely demise in an assassination in May 1989, but it is impossible to pinpoint precisely how many, since none of the editions are dated. Today, in France at least, the Dār al-Kitāb al-Lubnānī edition is not easily available. It is only occasionally offered by antiquarian booksellers at a very high price.

Among the reasons for the disregard of this edition might be the wide availability of Masson’s original work. Another likely explanation has to do with the fact that today’s French-speaking Muslims and Islamic publishers have many works by Muslim translators to choose from, whereas in 1980 only a few were available, and none of these were both stylistically convincing and theologically acceptable to the majority of the (Sunni) Muslim population of France. Thus, ‘Islamicising’ Masson’s fluent and readable translation might, at the time, have appeared to be the best solution to a problem that has since then been resolved, given the large number of revised and original translations by Muslims that have been published in the past three decades.

Johanna Pink