The most recent translation of the Qur’an into Russian, produced by the Kazan Muftiyat in 2019, can tell us much about Muslim theological polemics in contemporary Russia. Widely discussed on social media, the Kalam Sharif translation claims to be the only Sunni “orthodox” translation of Qur’anic meanings corresponding to Maturidi/Ashari theology.

As well as the print version with concise footnotes, Kalam Sharif is also available for free online and in audio format on Telegram, though without the explanatory commentaries. The language is intentionally simple and accessible. The preface provides an overview of the compilation of the sacred text and its features. Kalam Sharif is also concerned to prove the possibility of ‘proper’ translation, and it also equips its readership with the methodology of the anti-literalist approach, prominently demonstrated in the section dedicated to istawā.

While the work is explicitly associated with the Kazan Muftiyat, the full list of translators is not provided. Rather, the blurb presents the translation as “the result of seven years of collective work of qualified specialists: philologists, imams, teachers of Islamic educational institutions”. Nevertheless, we can identify some of the translators through their public statements in the media. Among them are the current young mufti of Tatarstan, Kamil-hazrat Samigullin, and Ahmad Abu Yahya, a Russian convert active on social media. Both have studied abroad and represent a new generation of Muslims who go beyond the traditional way ‘Soviet-style’ clerics speak about Islam in their rhetoric and approach.

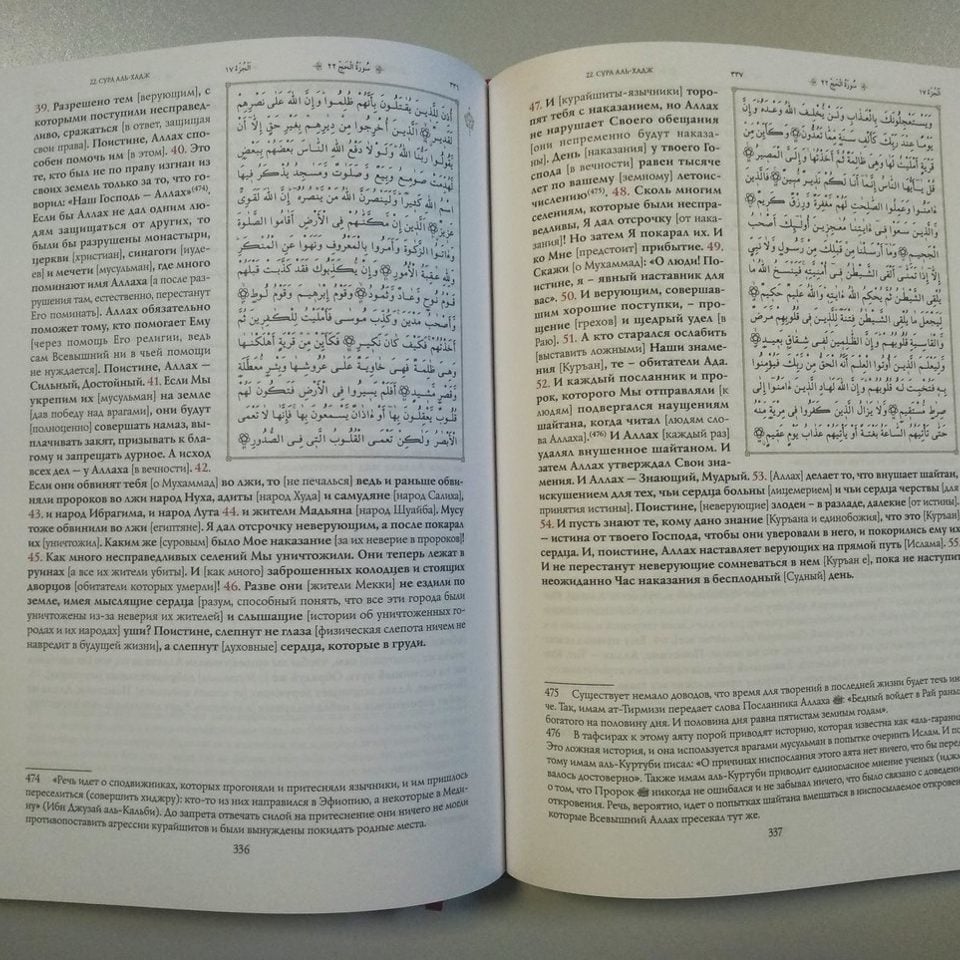

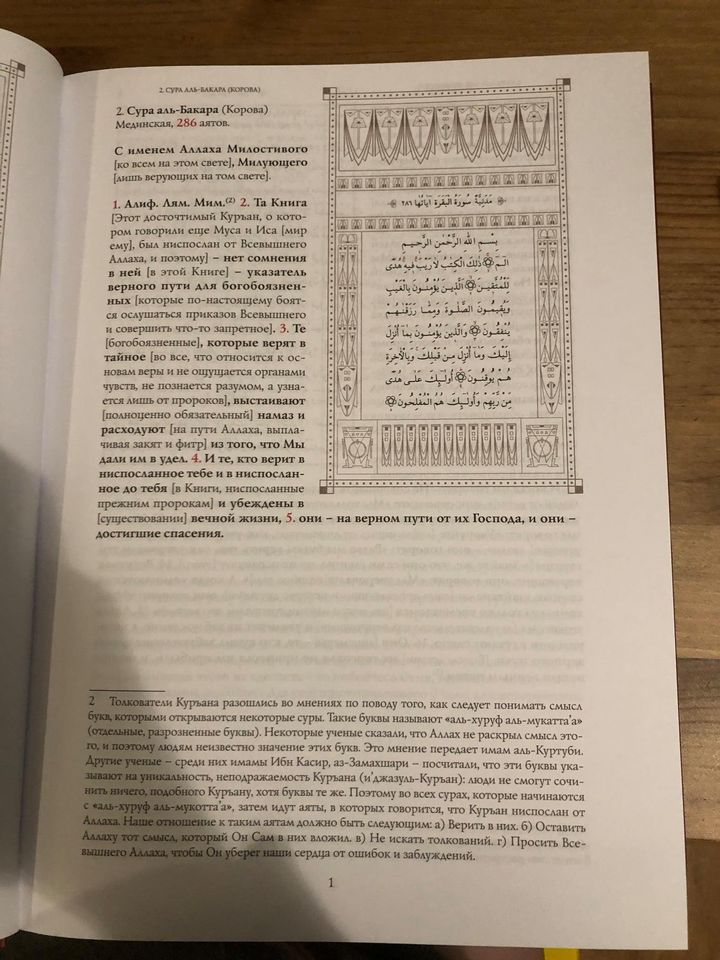

The aesthetically organised pages of this new Russian translation are combined with the original Arabic text and short footnotes which are mostly based on two types of sources. The first is contemporary scholars of ‘authoritative geography’ for translators, such as the conservative-oriented Turkish Sufi shaykh Mahmud Ufi (a.k.a. Mahmut Ustaosmanoğlu/Mahmut Efendi, b. 1929) and the Syrian exegete Muhammad Ali al-Sabuni (b. 1930). The second type of source is ‘classics’ such as Tafsir al-Jalalayn and the tafsirs of al-Tabari, al-Maturidi, Ibn Kathir, al-Qurtubi and others. An unusual choice is the Ottoman Iraqi exegete Mahmud al-Alusi, who appears in Kalam Sharif but was not commonly used in the post-Soviet milieu.

According to Ahmad Abu Yahya’s public statement, “Sunni Muslims [of Russia] did not have their translation” that would satisfy their demands and this became a guiding imperative for this work. Aiming to dismiss previous translational attempts, Kalam Sharif emphasises their “translation errors” [oshibki perevodov] throughout the preface and highlights previous translators’ ‘wrong’ choices. The array of adversaries against whom the new translation is premised includes old missionary works, ‘Orientalists’, and especially Salafi-oriented translations. The new translation’s anti-Salafi orientation is conjoined with the state-created binary discourse of “traditional Islam” vs “non-traditional,” where “traditional” is a hollow concept structured around loyalty to the political trajectory of modern Russian state. The Kazan Muftiyat, therefore, utilized this “traditional Islam” as a discursive space to promote its project of constructing its own version of Sunni orthodoxy. It also allows for alliances to be made: for example, the translation begins with a page of approval from the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Dagestan (SAMD), which was previously known for its opposition to the whole practice of Qur’anic translation, prominently after the Osmanov translation of the Qur’an (1995/1999/2007). Also, the references to contemporary Muslim exegetes of Turkey and Syria such as al-Sabuni and Mahmut Efendi are indicative of the poles of modern Kazan’s tradition. The mention of paradigmatic figures of Islamic history, such as al-Hasan al-Basri, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali and Tatar’s own Imam Shihabuddin Mardjani, also helps us to understand the Kazan Muftiyat’s outlook.

Significantly, the translation is devoid of Sufi allusions, despite the seeming association with pro-Sufi Dagestan and Turkey. It is also important that Kalam Sharif is not so much concerned with contemporary issues such as the place of women in modern societies, the issues of science and religion, and coexistence with people of other faiths in the modern nation-state. These issues are rarely discussed throughout Kalam Sharif, proving that the general outlook of “traditional Islam” is mostly arranged within the ‘safe’ space of religious polemics. The polemics allow the Kazan Muftiyat a clear self-assertion and influence on a certain category of Muslims in line with its outlook. The side-effect of this approach is that this strong emphasis on self-assertion, combined with the particular rendering and fixed interpolations, does not allow the plurality of interpretations that could be mentioned in the comments.

The Arabic text is well integrated into Kalam Sharif’s pages, thus making it useful for readers to combine translation with devotional reading. It also helps Islamicists to explore the translators’ strategy and the particular theological rendering of mutashābihāt verses. Overall, Kalam Sharif is promising to become a popular translation, and it opens the possibilities to analyse the extent of Russian contemporary Islamic discourse to fit in the theological strand of Maturidism.

Elvira Kulieva